Exploring Modern Reasoning-Enabled Large Language Models for Language Understanding

- Degree Programme: MSc Artificial Intelligence

- Module: Individual Project (7CCSMPRJ)

- Supervisor: Dr. Helen Yannakoudakis

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Helen Yannakoudakis, for her excellent guidance and support throughout this project. Her advice was essential to my success.

I am also grateful to the authors of the ITALIC dataset for making their work public. A special thanks to Matteo Rinaldi for providing access to the Mult-IT dataset.

I want to thank my peers, Jenny Kong, Tomasz Bernacki, and Jamie Ogundiran, for the helpful discussions we had about the general field of cultural alignment in LLMs.

Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their constant support and encouragement.

ABSTRACT

This project investigates the performance gap between cultural knowledge and linguistic understanding in smaller Large Language Models (LLMs) for the Italian language. While models often possess broad cultural knowledge, they can struggle with specific language rules like morphology, orthography and general grammar.

The project delivered two novel contributions. The first was analytical, exploring whether the reasoning capabilities of modern reasoning-capable LLMs (typically used for mathematics and programming) could be applied to the largely unexplored domain of linguistics. This investigation confirmed that enabling a model's step-by-step "thinking" process significantly improved its performance on complex linguistic tasks, proving reasoning is a valuable tool for language understanding.

While effective, the reasoning process is slow and computationally expensive, making it impractical for many applications. The project therefore attempted to improve the models' faster, non-reasoning mode through standard LoRA fine-tuning. This successfully improved linguistic skills but also created a critical problem as the models completely lost their ability to "think". The project's second novel contribution was a technical solution to this trade-off: a hybrid training method. This technique fine-tunes models using a mixed dataset, combining standard question-answer pairs with synthetically generated Chain-of-Thought (CoT) examples from the target model itself.

This hybrid approach was highly successful. It enhanced linguistic performance in the fast, non-reasoning mode while also fully preserving and even improving the models' advanced reasoning capabilities. The result is a more effective and versatile tool for the Italian language.

NOMENCLATURE

| Symbol / Acronym | Description |

|---|---|

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| RLVR | Reinforcement Learning through Verifiable Rewards |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| PEFT | Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning |

| LoRA | Low-Rank Adaptation |

| B | Billion parameters |

| CoT | Chain-of-Thought |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| NLU | Natural Language Understanding |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RLHF | Reinforcement Learning via Human Feedback |

| ToT | Tree of Thoughts |

| CoD | Chain of Draft |

| CISC | Confidence-Informed Self-Consistency |

| SFT | Supervised Fine-Tuning |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| GRPO | Group Relative Policy Optimisation |

| FFT | Full Fine-Tuning |

LIST OF TABLES

Table 9.1: Baseline Replication Results for Llama 3.1 8B Ita

| Category | Replicated Result (%) | Reference Result (%) | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Art | 70.78 | 70.10 | +0.68 |

| Civic Education | 71.50 | 71.22 | +0.28 |

| Current Events | 82.70 | 82.61 | +0.09 |

| Geography | 79.06 | 79.26 | -0.20 |

| History | 77.66 | 77.40 | +0.26 |

| Literature | 67.17 | 67.17 | 0.00 |

| Tourism | 71.33 | 71.73 | -0.40 |

| Lexicon | 81.31 | 81.51 | -0.20 |

| Morphology | 51.71 | 52.14 | -0.43 |

| Orthography | 52.29 | 53.04 | -0.75 |

| Synonyms | 81.27 | 81.15 | +0.12 |

| Syntax | 53.52 | 53.65 | -0.13 |

| Total | 70.32 | 70.49 | -0.17 |

Table 9.2: Baseline Replication Results for Mistral NeMo

| Category | Replicated Result (%) | Reference Result (%) | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Art | 66.02 | 66.33 | -0.31 |

| Civic Education | 69.71 | 69.27 | +0.44 |

| Current Events | 82.52 | 82.61 | -0.09 |

| Geography | 76.43 | 76.00 | +0.43 |

| History | 74.95 | 74.34 | +0.61 |

| Literature | 69.31 | 68.39 | +0.92 |

| Tourism | 67.45 | 67.76 | -0.31 |

| Lexicon | 79.90 | 79.37 | +0.53 |

| Morphology | 52.86 | 52.86 | 0.00 |

| Orthography | 56.23 | 55.61 | +0.62 |

| Synonyms | 74.03 | 74.25 | +0.22 |

| Syntax | 54.57 | 54.78 | -0.21 |

| Total | 68.68 | 68.53 | +0.15 |

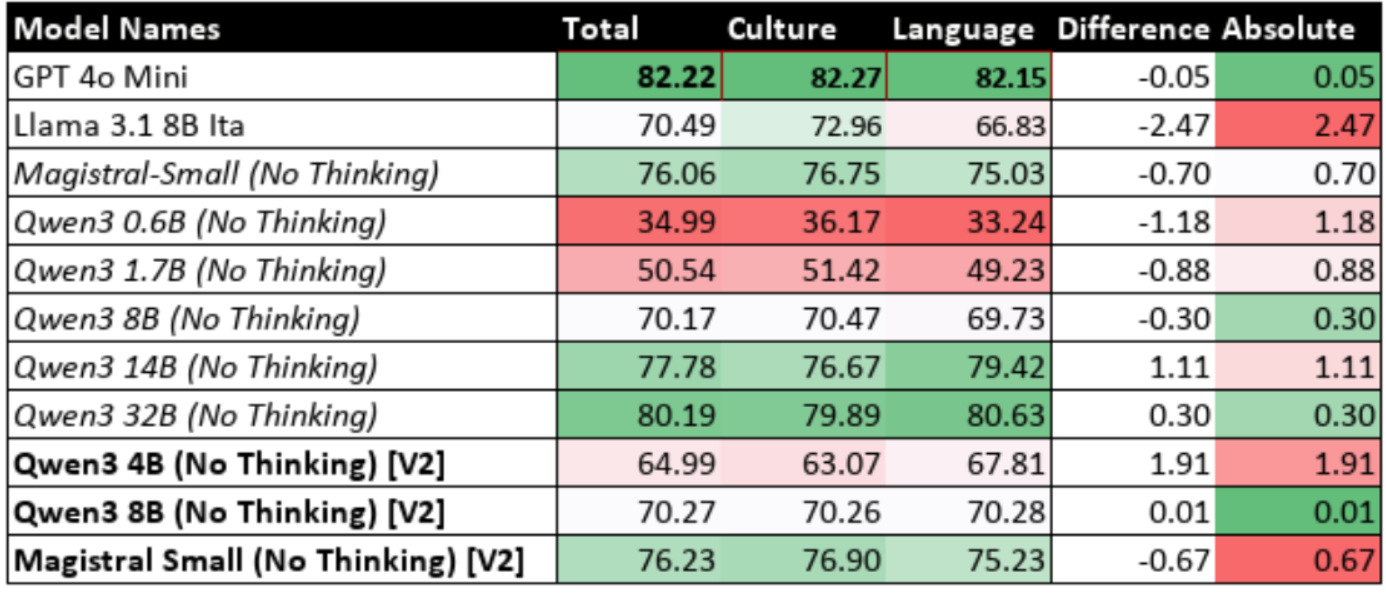

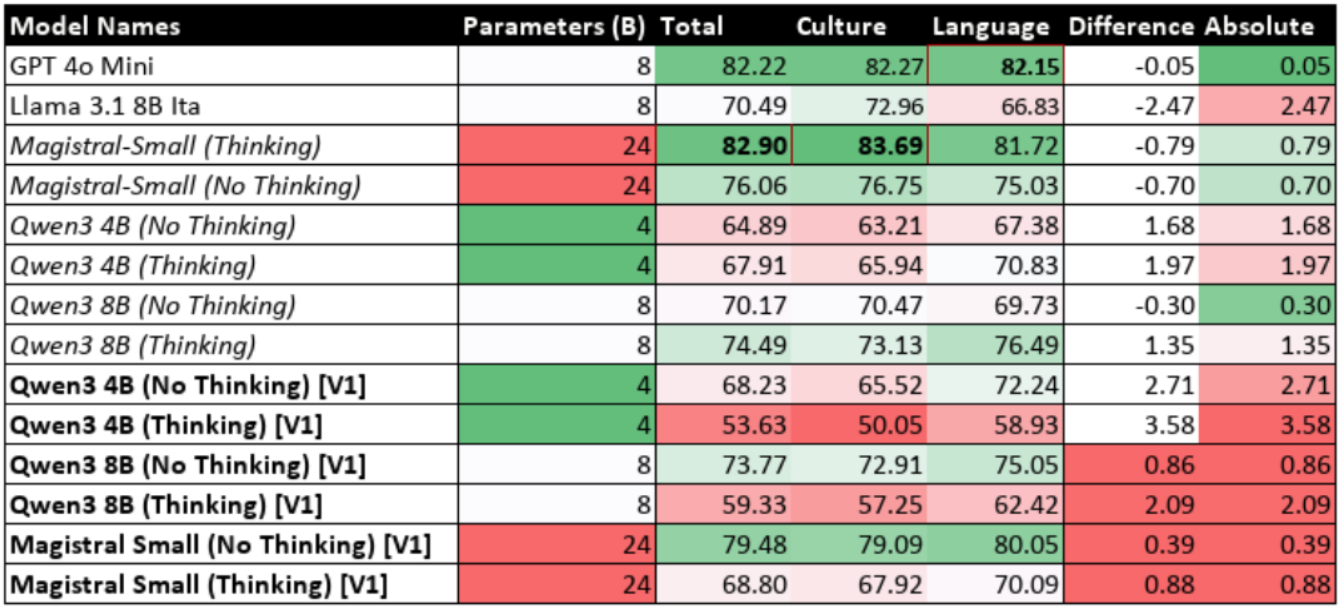

Table 9.3: Performance of Reasoning Models with Reasoning Disabled

Table 9.4: Performance Change with Reasoning Enabled (%)

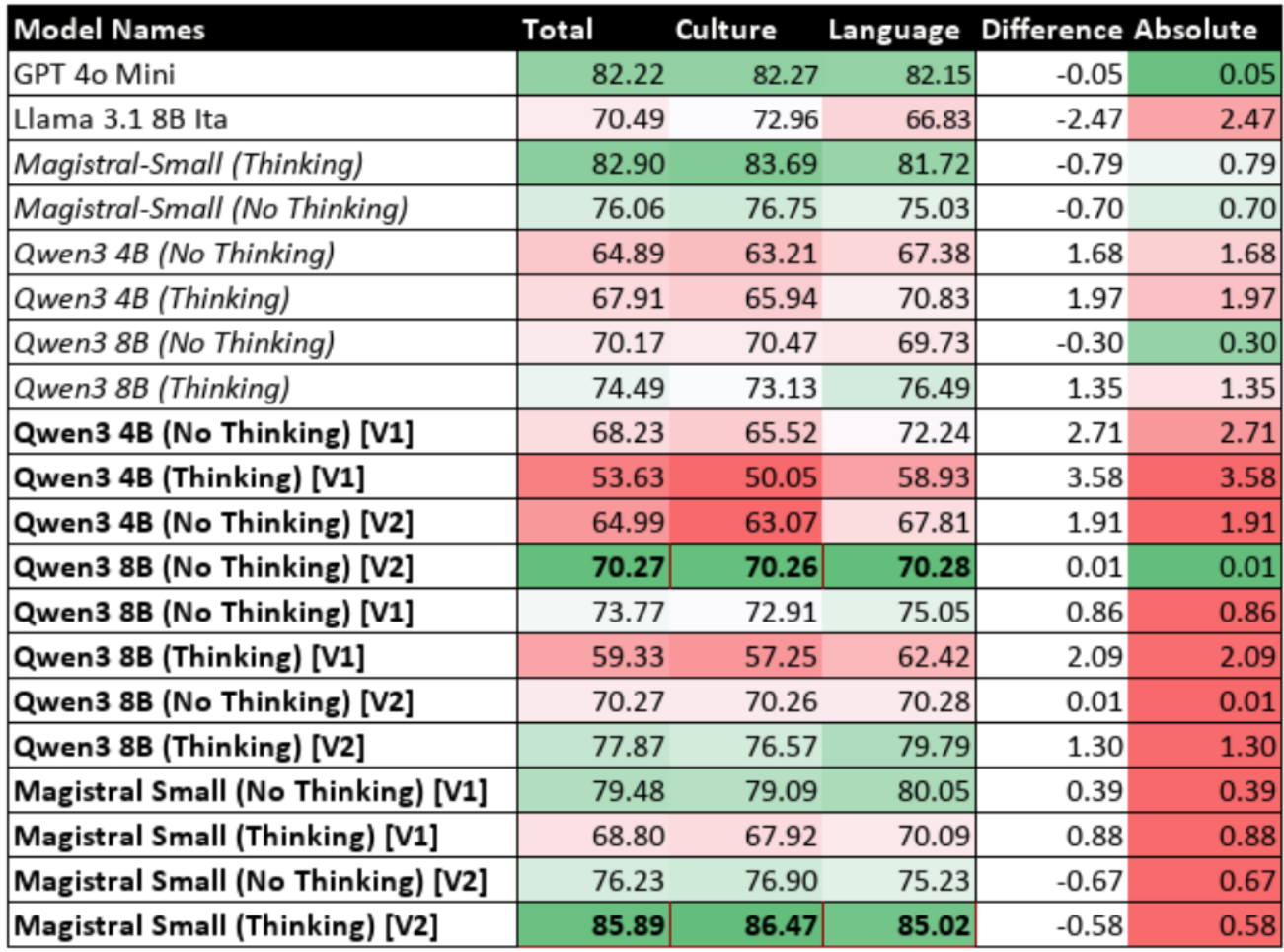

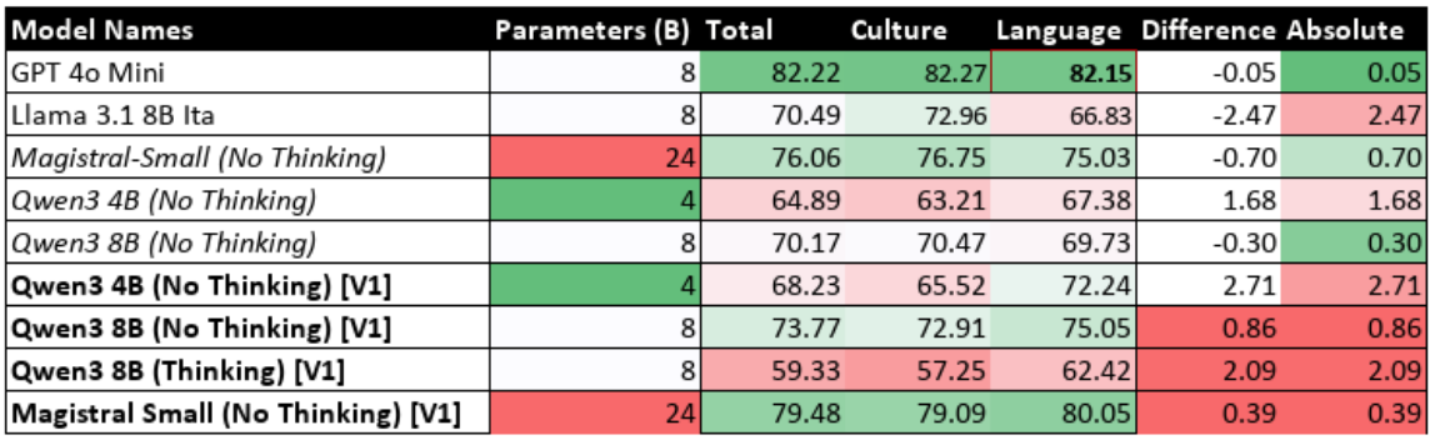

Table 9.5: Performance of Fine-Tuned Models with Reasoning Disabled (Iteration 1)

Table 9.6: Performance of Fine-Tuned Models with Reasoning Enabled (Iteration 1)

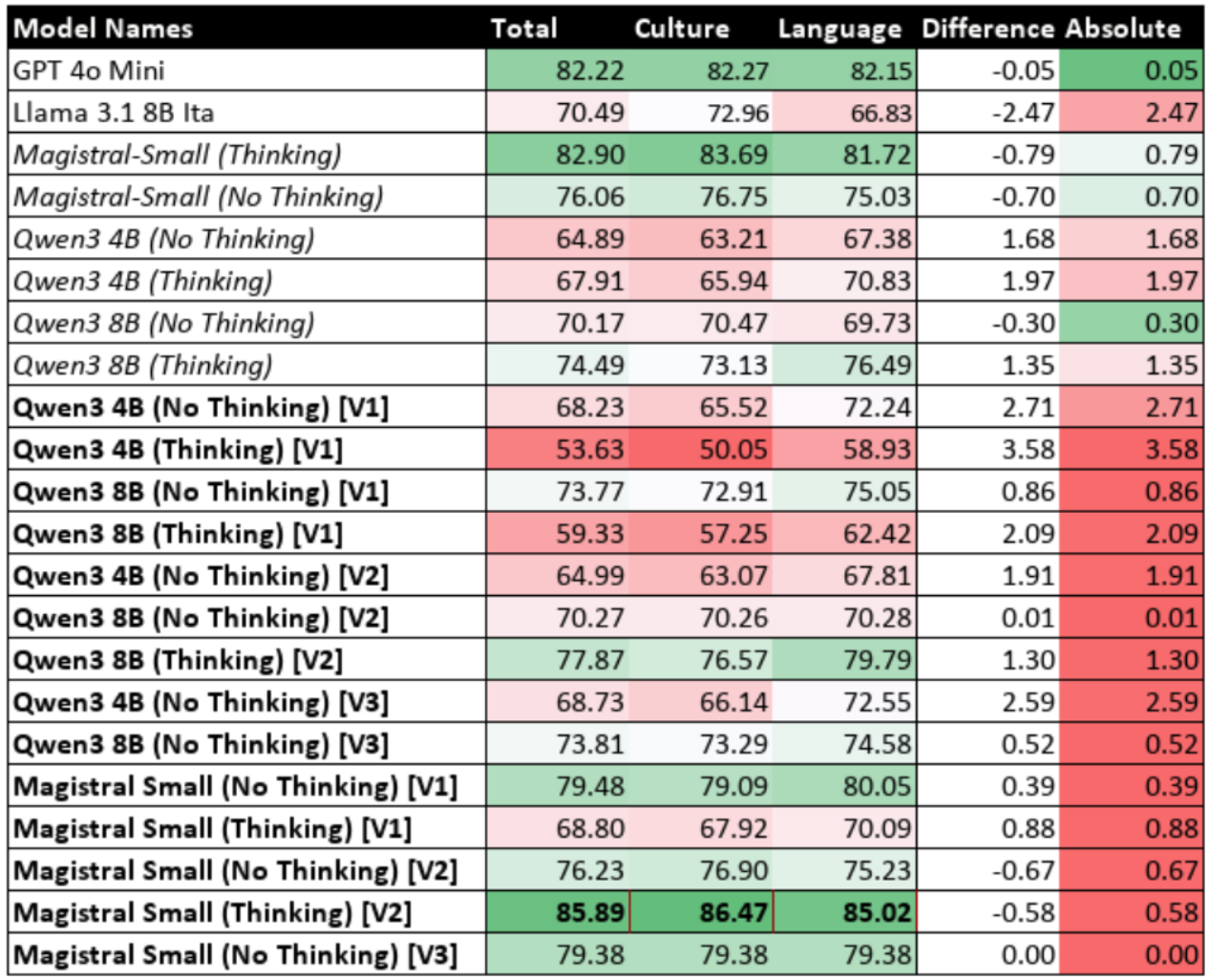

Table 9.7: Performance of Fine-Tuned Models with Reasoning Disabled (Iteration 2)

Table 9.8: Performance of Fine-Tuned Models with Reasoning Enabled (Iteration 2)

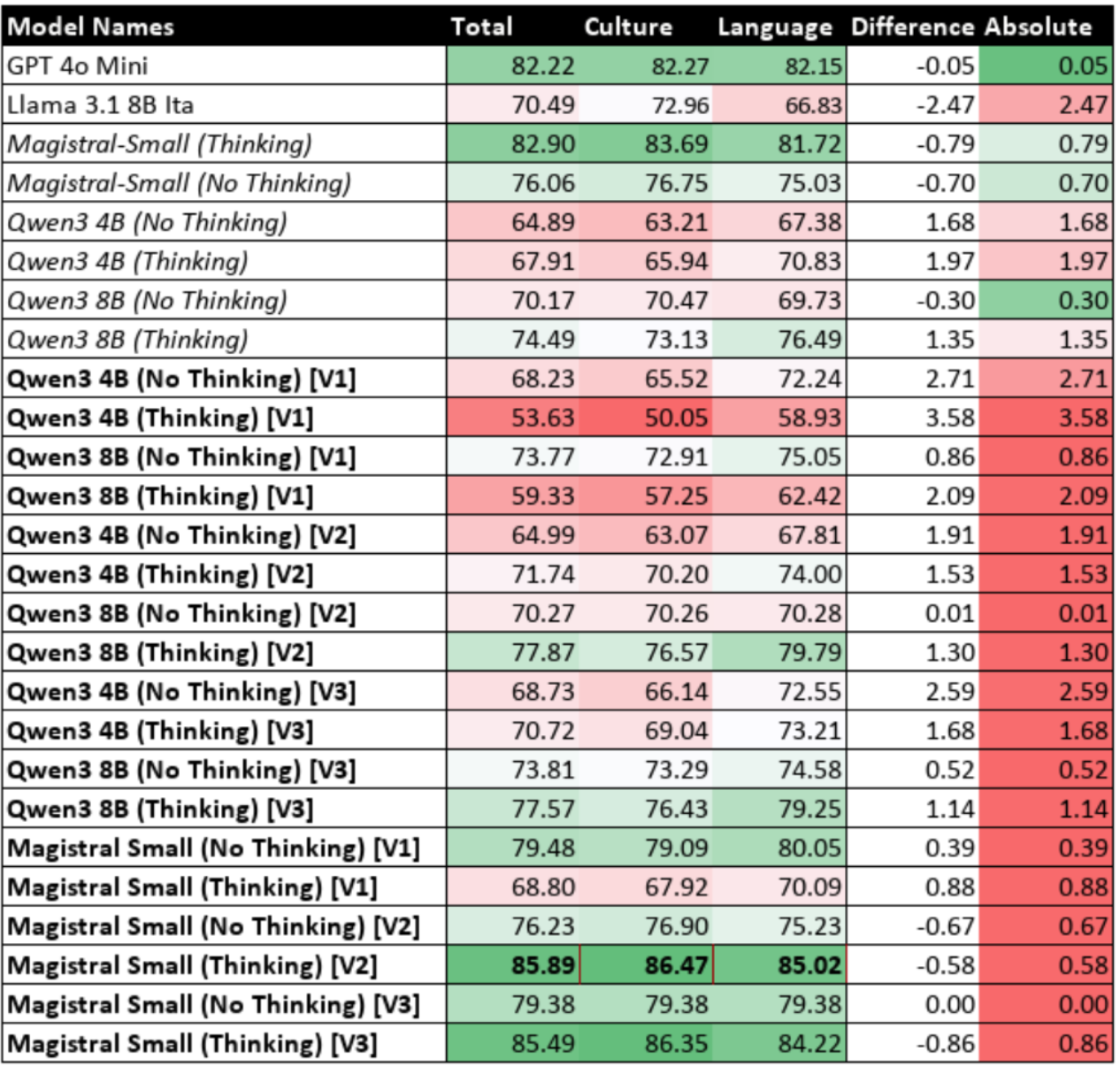

Table 9.9: Performance of Fine-Tuned Models with Reasoning Disabled (Iteration 3)

Table 9.10: Performance of Fine-Tuned Models with Reasoning Enabled (Iteration 3)

List of Figures

Figure 6.1: Experimental Pipeline Architecture

Figure 6.2: Fine-Tuning and Evaluation Cycle

Figure 6.3: Standard Pipeline

Figure 6.4: Synthetic Only Test Pipeline

Figure 6.5: Hybrid Training Pipeline

`

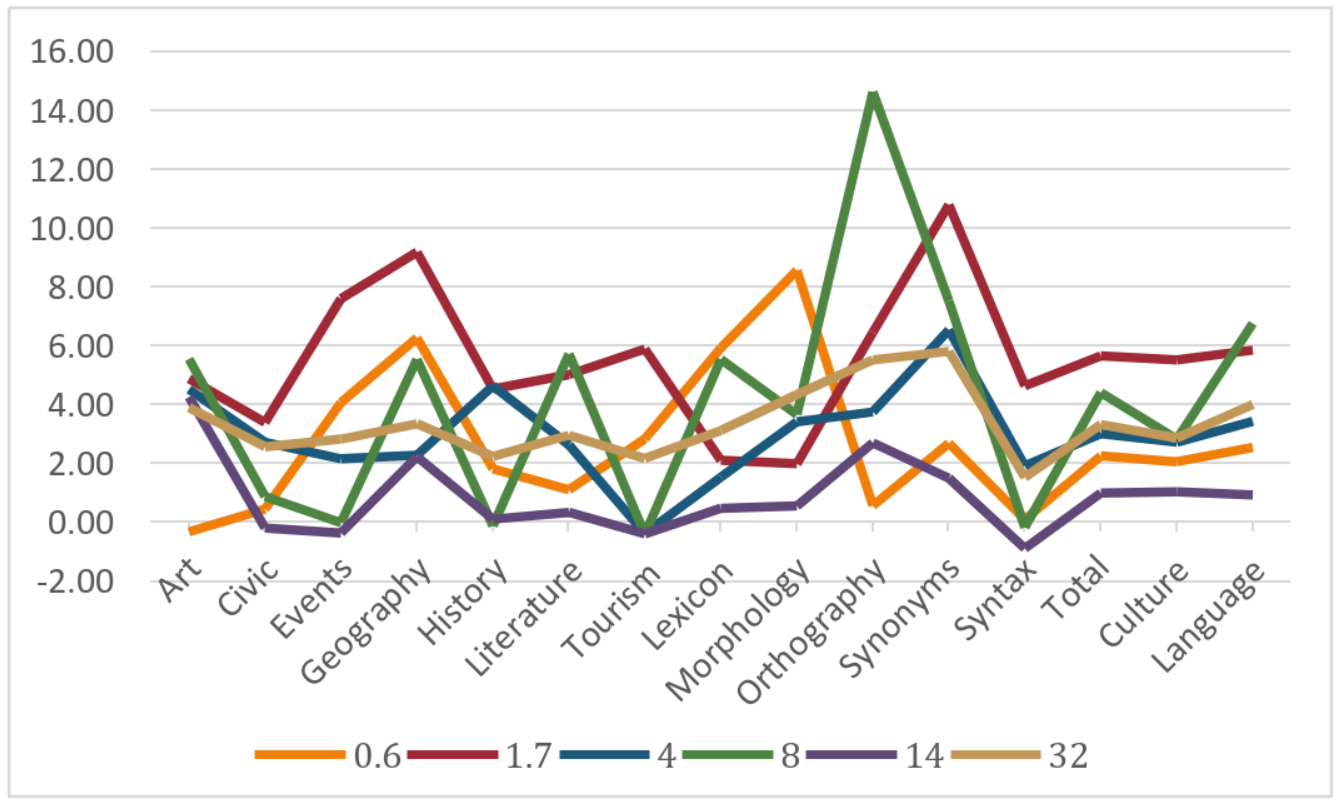

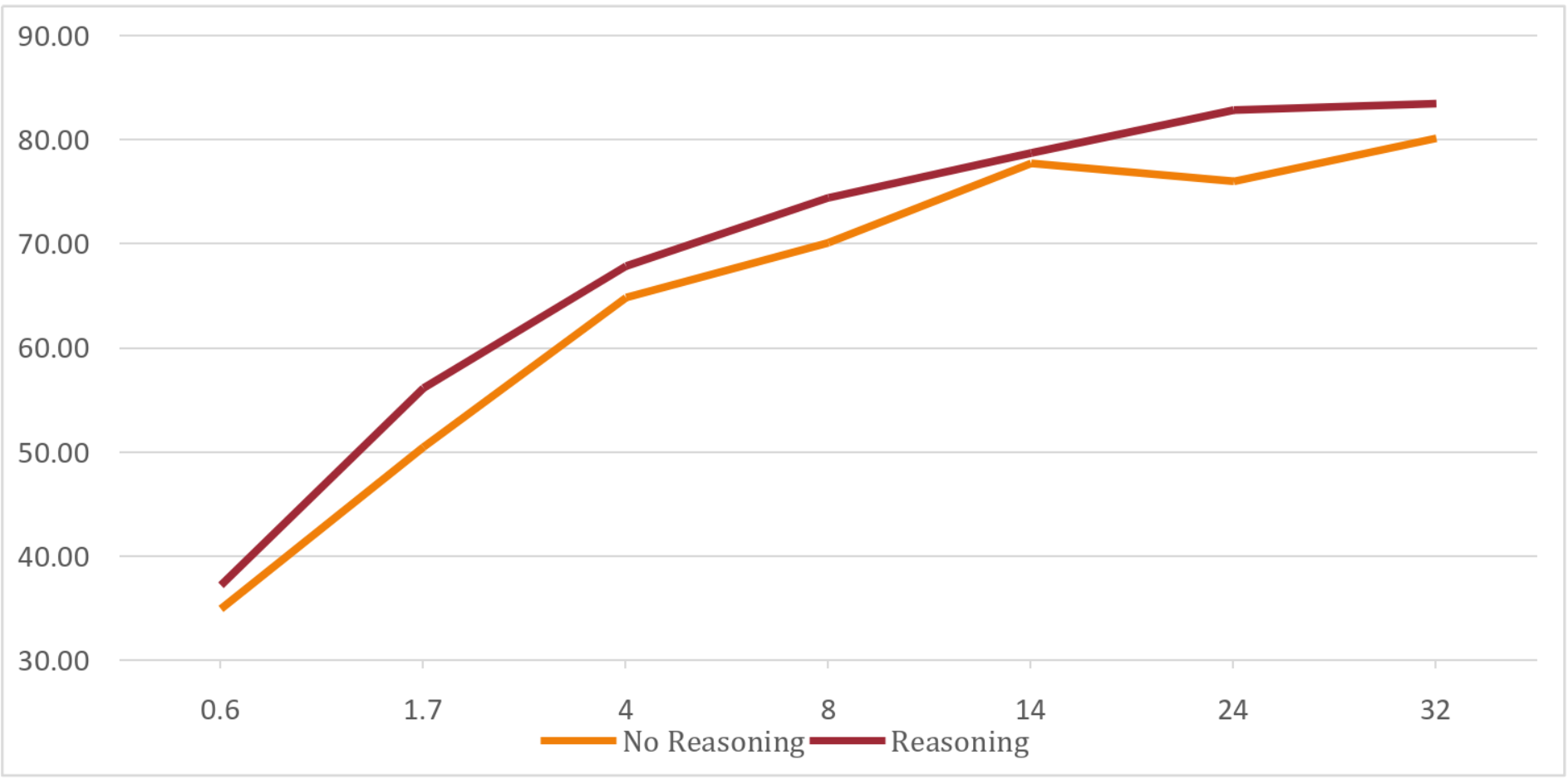

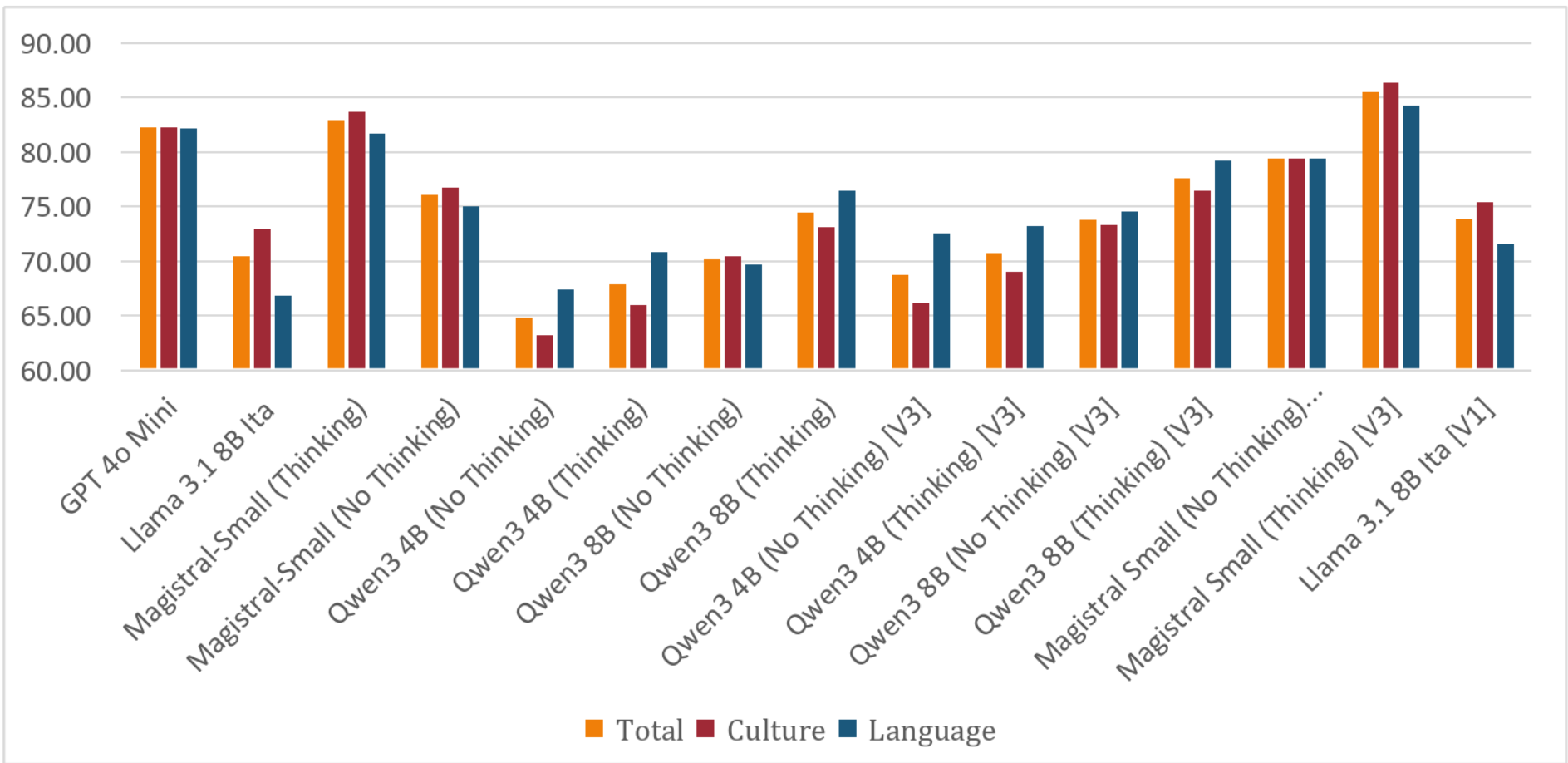

Figure 9.1: Performance Difference Between Reasoning and No-Reasoning States

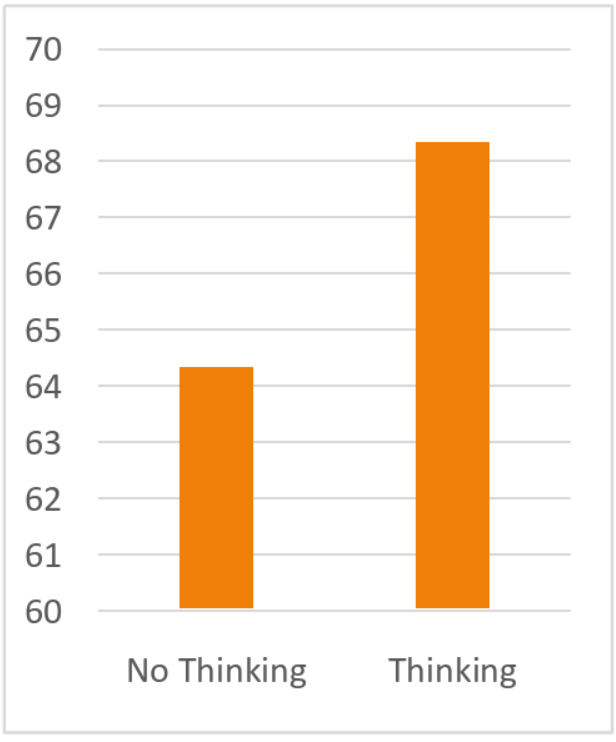

Figure 9.2: Average Difference Across Models for Reasoning & Non-Reasoning

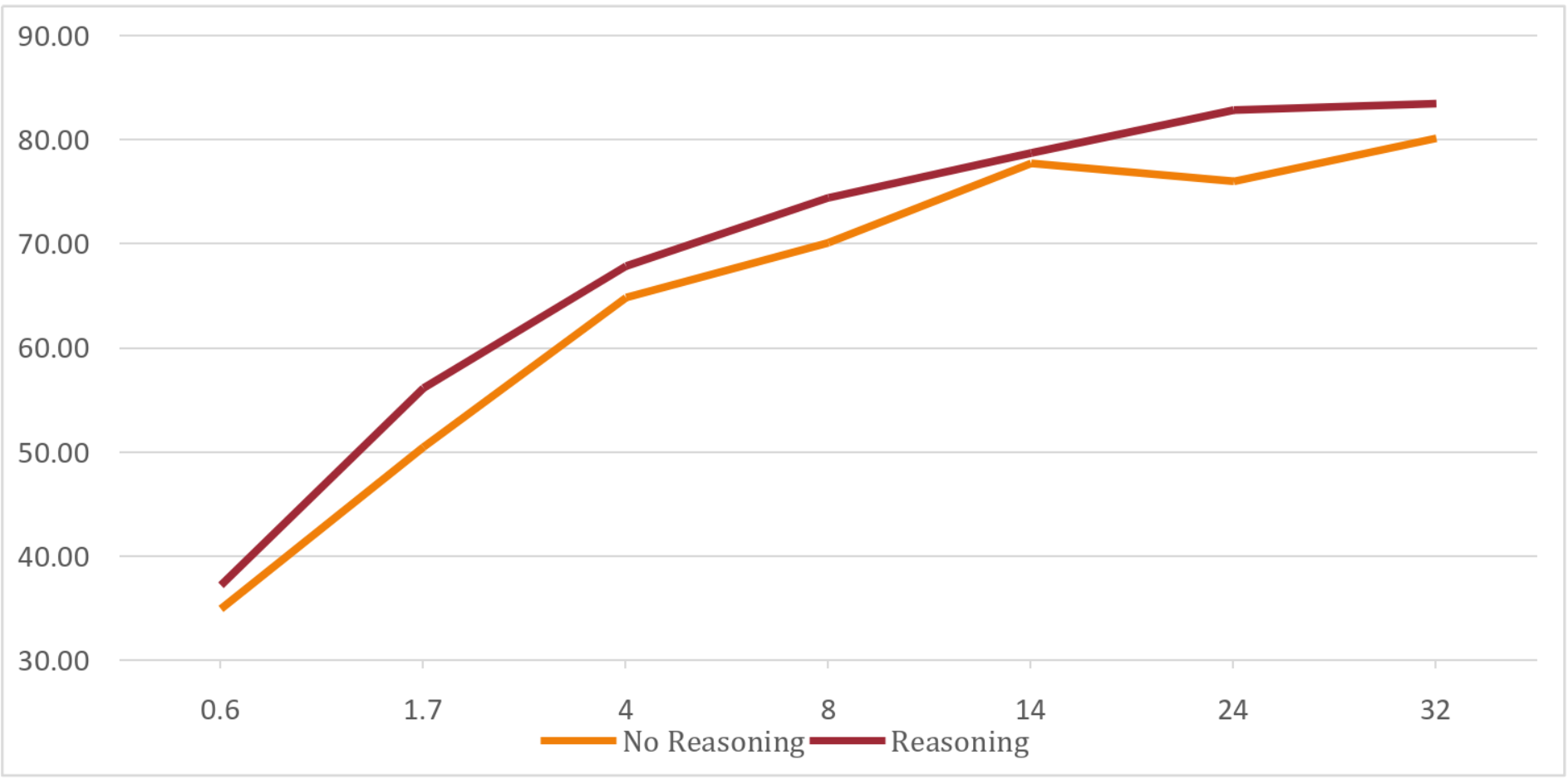

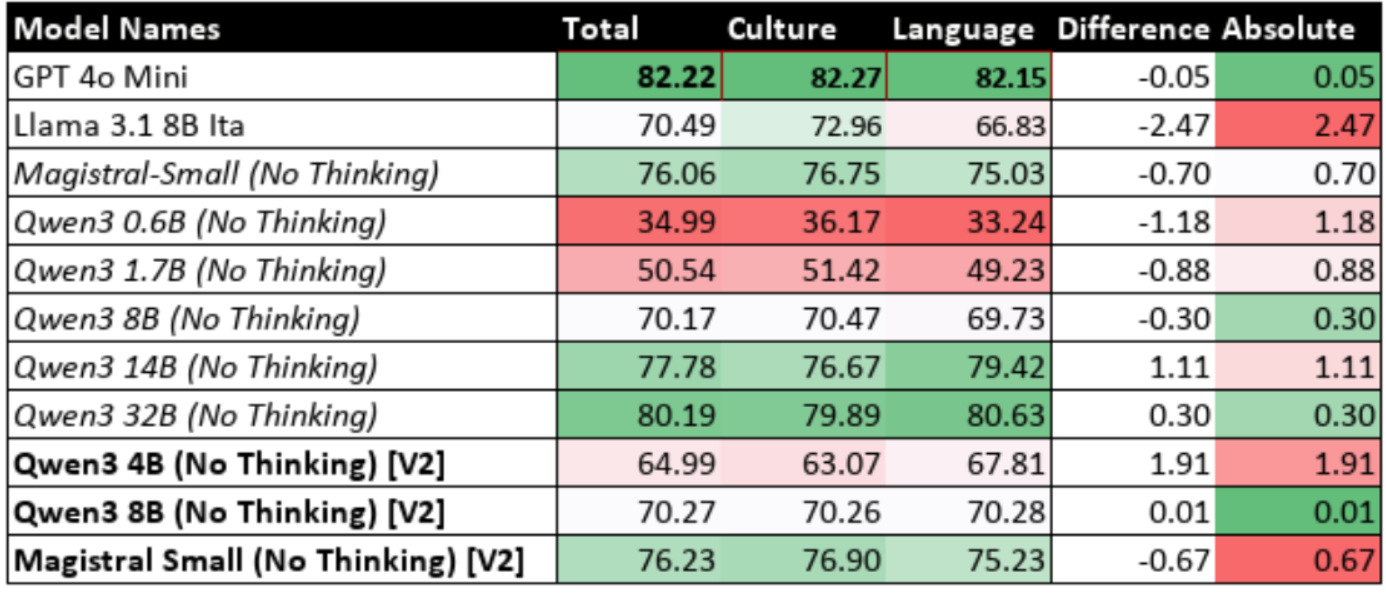

Figure 9.3: Accuracies for Reasoning & Non-Reasoning Based on Scale

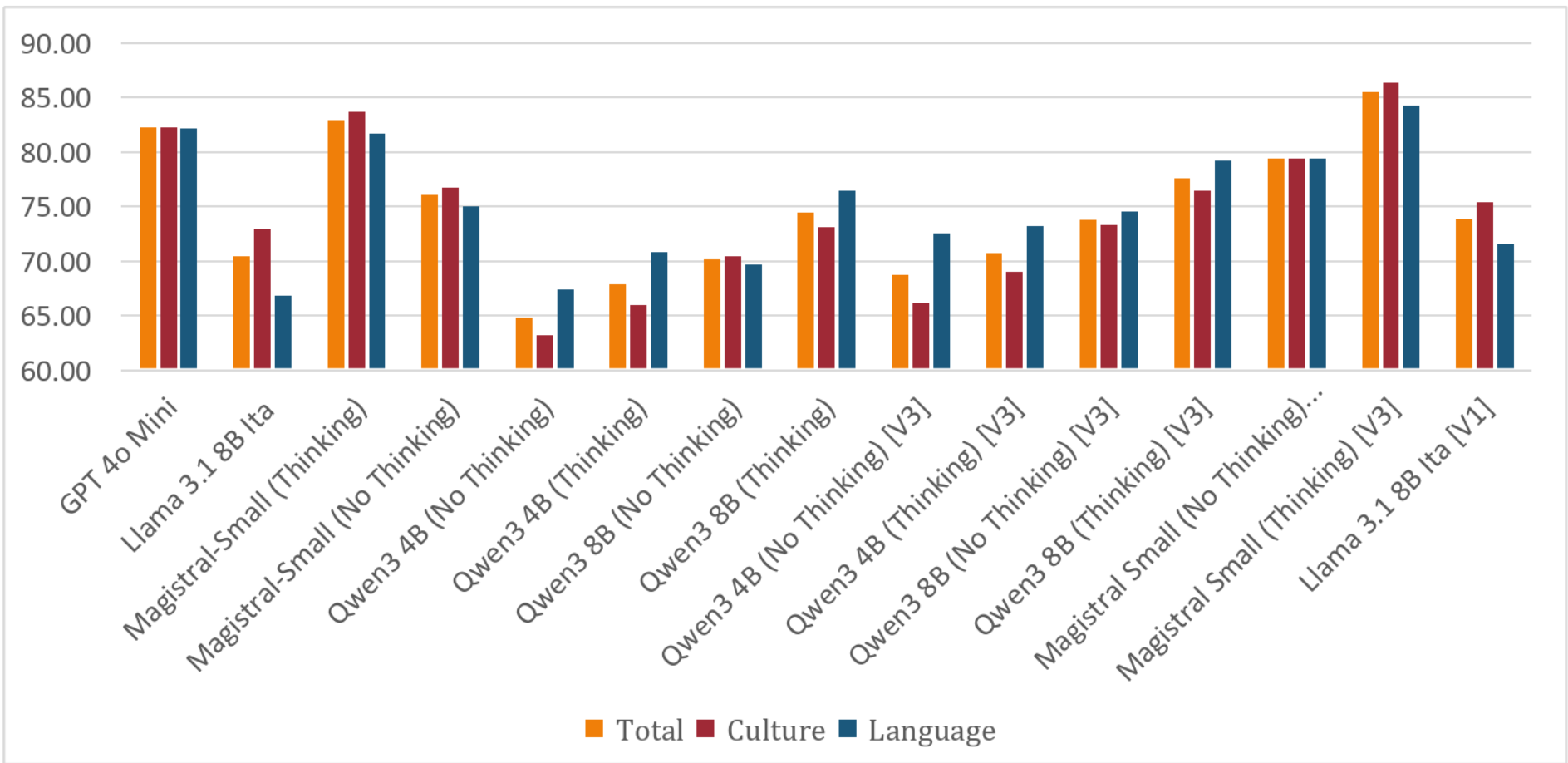

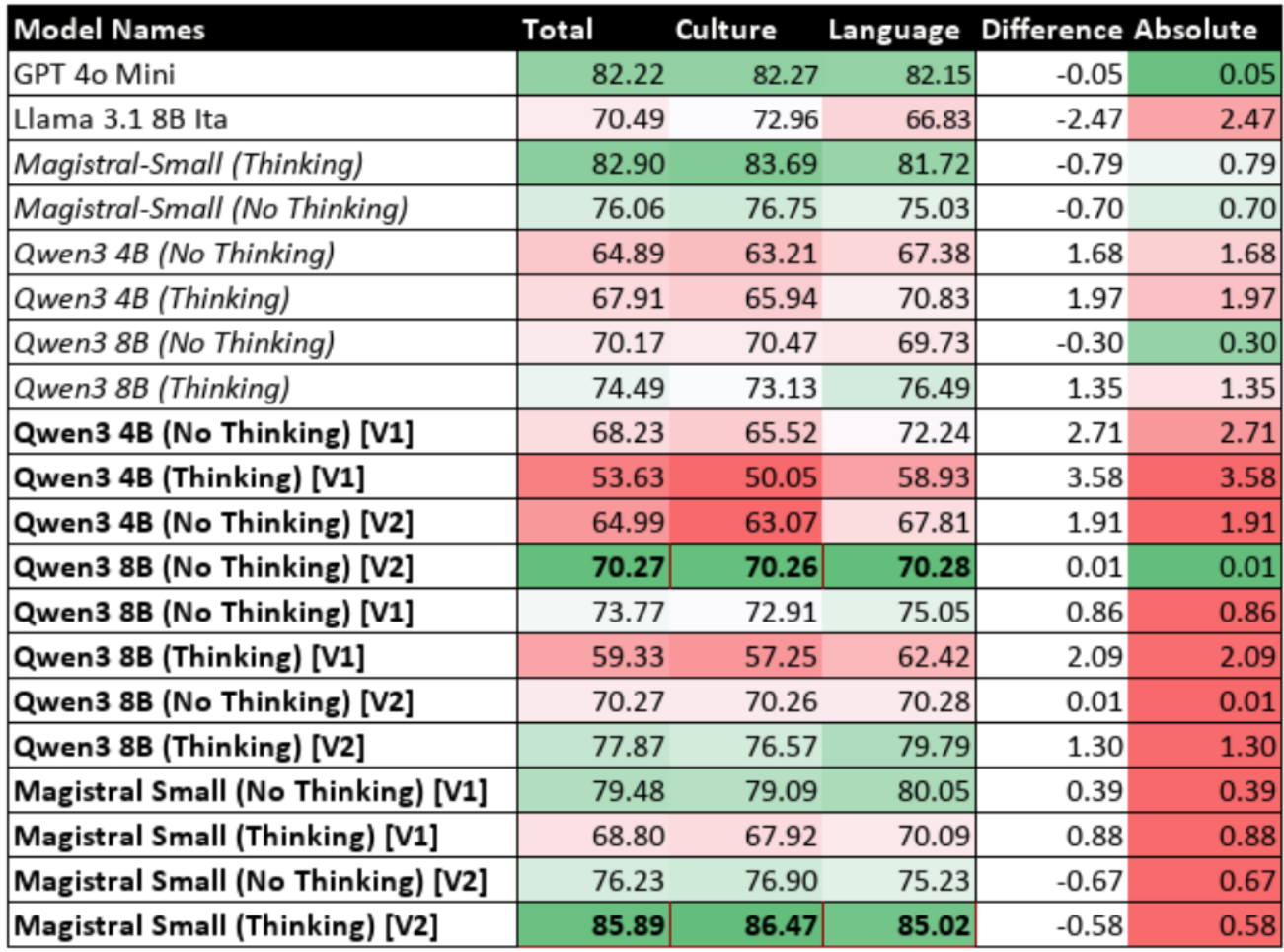

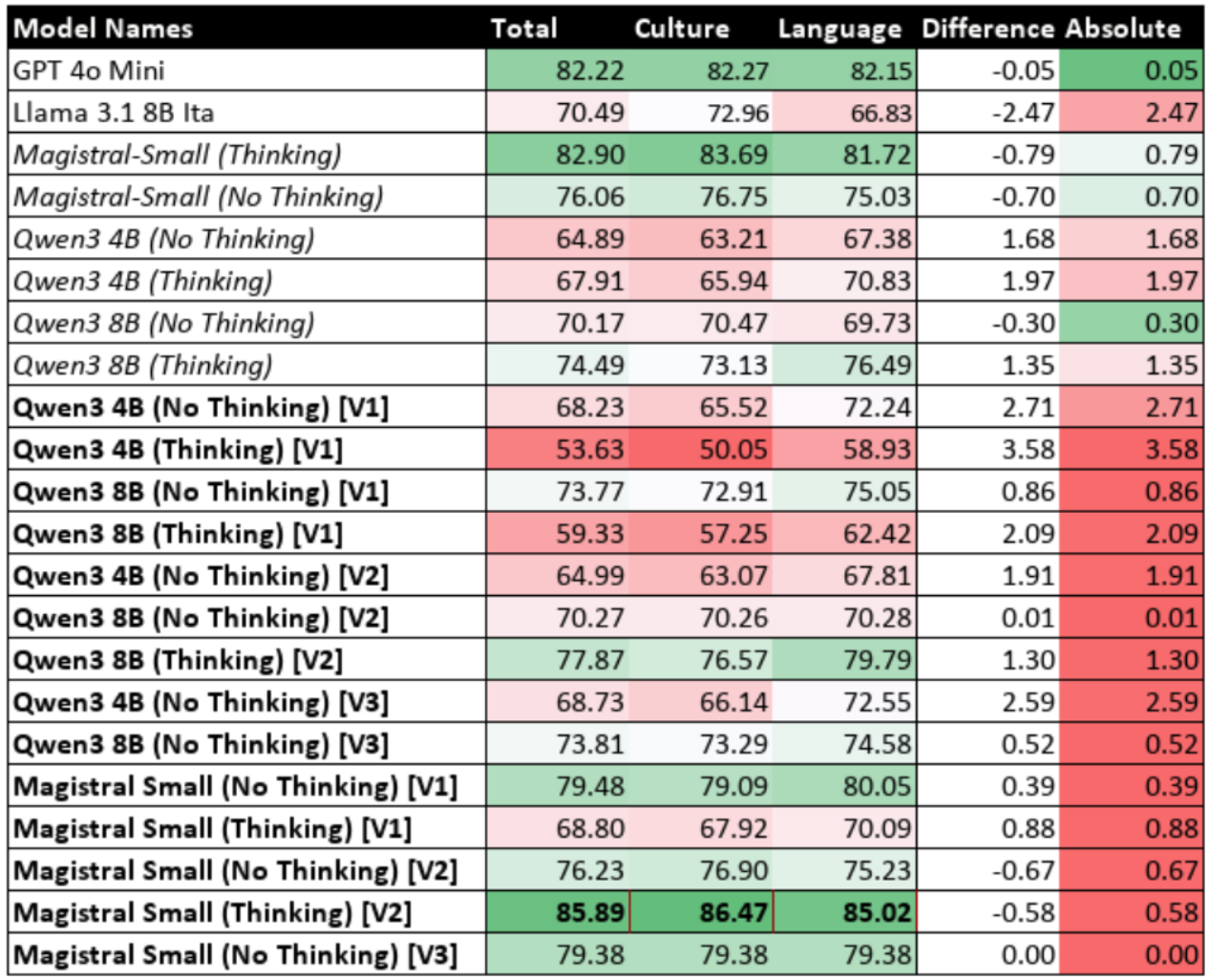

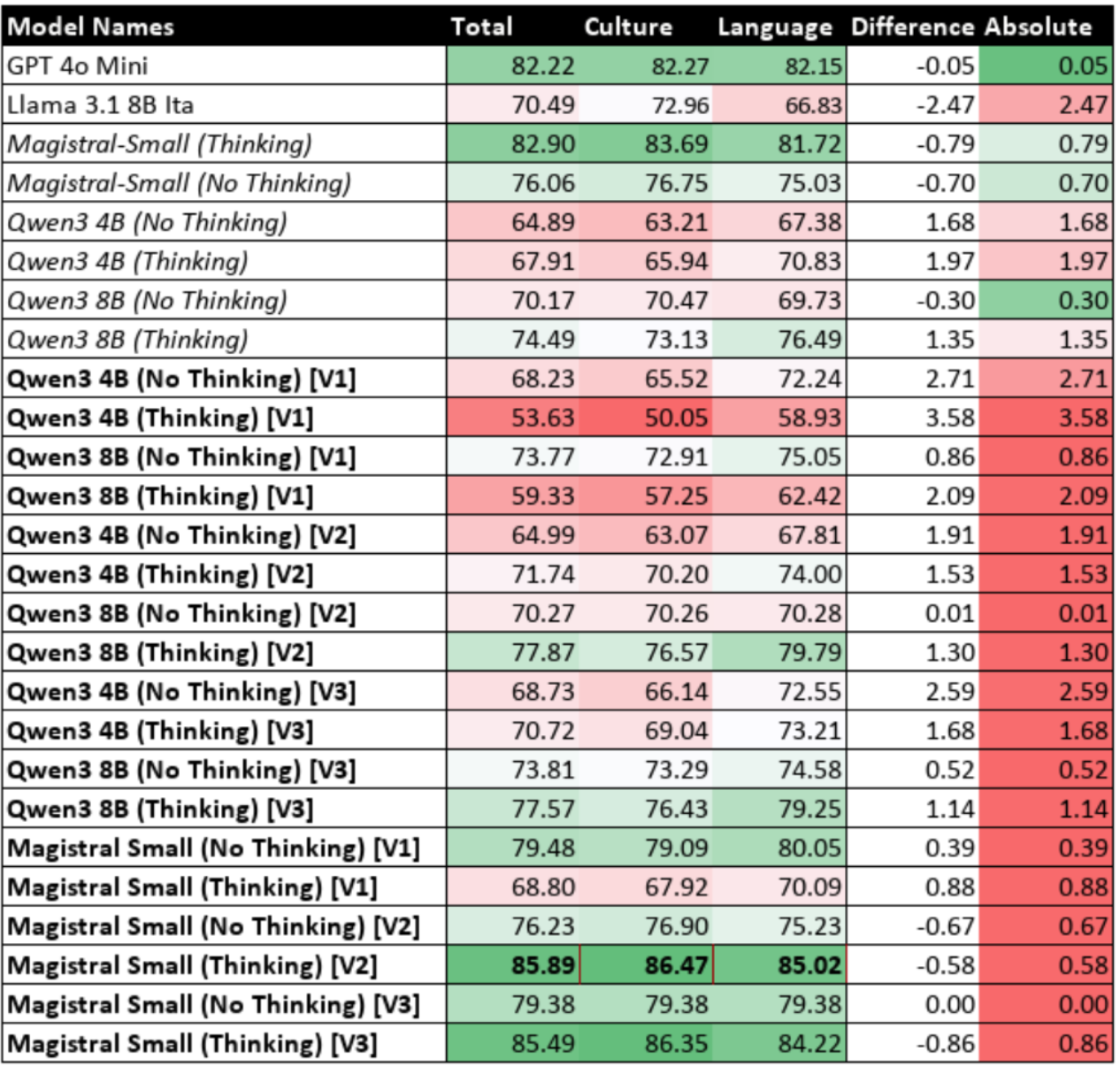

Figure 9.4: Summary of Model Accuracy Against Reference Models, Base Models and Fine-Tuned Models

1 - Introduction

1.1 - Background & Motivation

Recent advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) have led to their widespread integration into global digital services, from powering conversational search engines to automating customer support. For these models to be fair and effective, they must be culturally aware. However, current research shows a strong bias towards English and Western cultures, slowing adoption in other regions due to significant linguistic and cultural barriers [Seveso et al., 2025]. This has led to the development of native-language benchmarks, such as ITALIC for Italian, which provides a more authentic assessment of a model's capabilities.

This project focuses specifically on smaller LLMs, as their efficiency makes them critical for real-world deployment. Unlike their larger counterparts, which require substantial computational resources, smaller models are affordable for most companies to train and deploy in applications like customer service agents. For these tools to be effective, they must be linguistically aligned to sound natural. Similarly, for home users running assistants locally for everyday tasks, cultural and linguistic alignment is essential for the technology to feel genuinely helpful.

1.2 - Research Problem

However, analysis using the ITALIC benchmark has revealed a critical and consistent discrepancy in these smaller models: they perform significantly better on tasks requiring general cultural knowledge than on those demanding a deep understanding of language-specific rules. The benchmark shows an average model accuracy of 75.03% on cultural tasks, which drops to just 63.12% on linguistic tasks. This performance gap is particularly wide in smaller, more efficient models, with foundational language skills like morphology and orthography being the weakest areas. This highlights a fundamental challenge: cultural knowledge does not guarantee linguistic competence. Crucially, existing research has focused on standard LLMs, leaving the potential for newer, reasoning-capable models to address this linguistic gap largely unexplored.

1.3 - Aims & Hypotheses

This project directly addresses this performance gap in smaller LLMs for the Italian language, guided by two central hypotheses. The first is that modern LLMs with reasoning capabilities may be better equipped to handle complex linguistic problems. This study makes a novel contribution by applying these reasoning methods to linguistics. Such models are typically used for tasks like mathematics and programming; their potential for language has been largely unexplored. However, activating these reasoning processes is computationally expensive and introduces delay, which is often impractical for real-time applications. Users interacting with customer service agents, for example, cannot wait for a lengthy thought process just for a grammatically correct response. This would also be expensive for businesses as more compute is being used.

This leads to the second hypothesis. While reasoning is effective, it is also slow and computationally expensive. The project therefore explored fine-tuning to improve the models' faster, non-reasoning mode. However, this revealed a critical trade-off: regular fine-tuning successfully improved linguistic skills but destroyed the models' ability to reason. The second hypothesis is that a novel hybrid training approach can solve this problem. This method uses LoRA and mixes a standard dataset with synthetically generated Chain-of-Thought (CoT) examples from the target model itself. The goal is to boost linguistic performance in the efficient non-reasoning mode, while also preserving the model's core reasoning abilities. This report will detail the investigation into these hypotheses, from a review of the relevant literature to the final analysis of the results and a discussion of their implications.

2 - Literature Survey

2.1 - Cultural Alignment in Large Language Models (LLMs)

Recent research highlights significant challenges in achieving cultural alignment in LLMs. Studies consistently show that current LLMs exhibit strong Anglocentric and Western-centric biases. They perform substantially better on English-language tasks while struggling with culturally-specific knowledge in underrepresented languages [Pawar et al., 2024; Rao et al., 2024]. This cultural misalignment stems primarily from training data composition. English and Western sources dominate these datasets, creating a risk of "cultural homogenisation" where anglocentric models become the default [Seveso et al., 2025].

The problem extends beyond simple translation. Even perfectly translated benchmarks can be culturally biased. For instance, an analysis of the widely-used MMLU benchmark found that a significant portion of questions requires culturally sensitive knowledge, with the vast majority of these being specific to North America or Europe [Singha et al., 2025]. This creates an unfair evaluation standard, as models are penalised for not mastering Western-centric concepts [Moroni et al., 2024; Seveso et al., 2025].

This has led to a key finding: a fundamental discrepancy exists between cultural knowledge and linguistic understanding in LLMs. While LLMs may possess broad cultural knowledge, this often fails to translate into a deep comprehension of language-specific rules, particularly in morphologically rich languages like Italian [Rao et al., 2024]. This gap becomes especially pronounced in smaller models, where linguistic tasks such as morphology and orthography present greater challenges than general cultural knowledge.

2.2 - Italian Language Model Research & Benchmarking

The Italian NLP community has historically lacked comprehensive evaluation benchmarks compared to English. Early Italian benchmarks focused primarily on classification-based tasks such as sentiment analysis and hate speech detection, failing to assess higher-level capabilities like commonsense reasoning [Basile et al., 2023; Lai et al., 2023]. This limitation has hindered the systematic evaluation of LLM performance in Italian cultural and linguistic contexts. In response, a new generation of more comprehensive, native Italian benchmarks has been developed. These include collaborative efforts like CALAMITA and evaluation suites such as ItaEval, which cover a wide range of tasks from hate speech to gender-neutral rephrasing [Attanasio et al., 2024a; Attanasio et al., 2024b]. However, many of these initiatives either combine multiple smaller datasets, which can complicate standardised testing, or rely on machine-translated content from English sources [Moroni et al., 2024].

The introduction of ITALIC [Seveso et al., 2025] represents a significant advancement. It was chosen for this project because it provides a single, comprehensive benchmark built from authentic, native Italian materials. It comprises 10,000 multiple-choice questions derived from Italian public examination materials, spanning 12 domains across two main categories: Culture and Commonsense (encompassing history, geography, literature, and civic knowledge) and Language Capability (covering syntax, morphology, orthography, and lexicon). Unlike benchmarks that rely on translated content, ITALIC's use of native sources provides a more authentic cultural and linguistic evaluation.

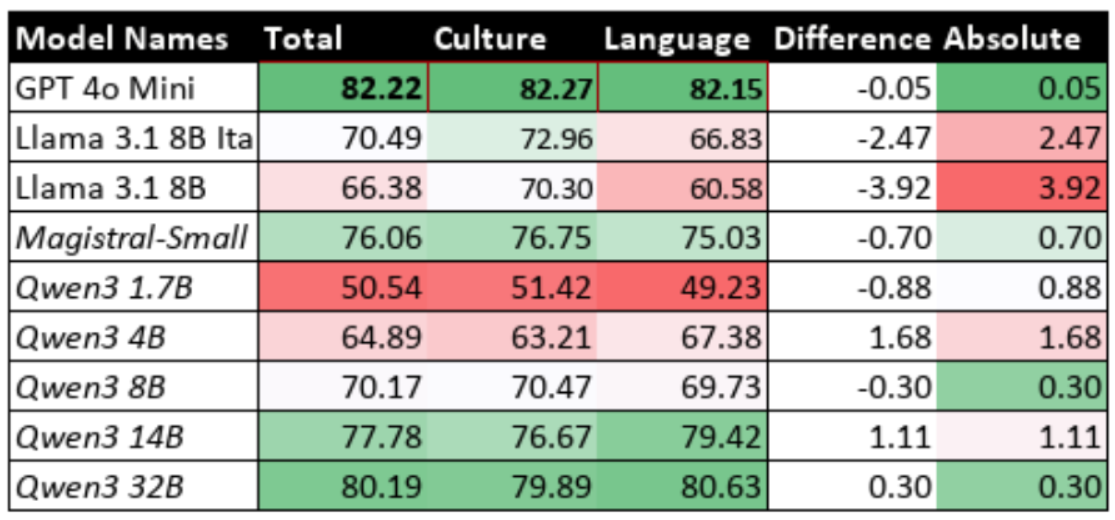

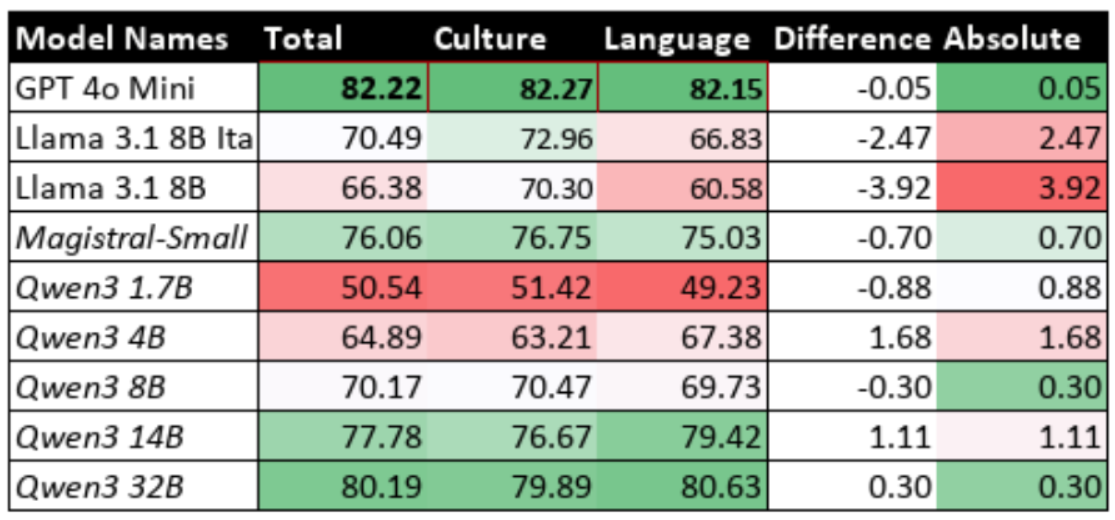

ITALIC's comprehensive evaluation of 17 models revealed systematic performance gaps [Seveso et al., 2025]. Models consistently performed better on Culture and Commonsense tasks (average 75.03%) compared to Language Capability tasks (average 63.12%). Morphology emerged as the most challenging domain (55.99% average accuracy), followed by orthography (62.09% average accuracy). This pattern held across both proprietary and open-weights models, indicating fundamental limitations in linguistic understanding rather than model-specific issues. Additionally, open-weights models tend to perform worse compared to their proprietary counterparts, with GPT-4o-Mini scoring 82.22% whereas Llama 3.1 8B Ita (fine-tuned on Italian) scores 70.49% and the standard Llama 3.1 8B scores 66.38%.

2.3 - Performance Characteristics of Smaller LLMs

Smaller-scale LLMs (5-35B parameters) face particular challenges in cultural and linguistic alignment. The ITALIC benchmark demonstrates clear scaling effects, with larger models generally outperforming smaller counterparts with Llama 3.1 405B scoring 88.89% whereas the smaller Llama 3.1 8B only scores 66.38% [Seveso et al., 2025]. However, the performance gap varies significantly across domains, with linguistic tasks showing steeper scaling curves than cultural knowledge tasks; this is proven by the difference between Culture and Common sense and Language Understanding, where the discrepancy between Llama 3.1 405B is 4.98% but the discrepancy for Llama 3.1 8B is 9.72%.

Among smaller models, the Llama 3.1 8B provides instructive examples. The base multilingual Llama 3.1 8B achieved 66.38% overall accuracy on ITALIC, with notable weaknesses in morphology (40.00%) and orthography (49.33%) [Seveso et al., 2025]. The Italian-specific fine-tuned variant (Llama 3.1 8B Ita) showed modest improvements to 70.49% (+4.11%) overall, with the largest gains in Language Capability tasks (+6.25 percentage points) compared to Culture and Commonsense (+2.66 percentage points).

More specifically, Llama 3.1 8B Ita achieved 72.96% in Culture and Commonsense but only 66.83% in Language Capability [Seveso et al., 2025]. This reveals a substantial performance gap. After fine-tuning, the improvement for Culture and Commonsense was only 2.66%, while the improvement for Language Capability was a much larger 6.25%. This indicates significant potential for further enhancement in linguistic tasks. This pattern suggests that Culture and Commonsense knowledge is already well-established through cross-lingual training. Language Capability, however, requires more targeted native language training. Despite the larger improvement, Language Capability performance remains substantially below Culture and Commonsense levels (6.13% difference) which highlights the persistent challenge of linguistic understanding.

Morphology represents the most challenging domain across both Llama 3.1 8B variants, with the base model scoring only 40.00% and the Italian fine-tuned version achieving 52.14% [Seveso et al., 2025]. Orthography was the second weakest area, with the base model scoring 49.33% and increasing to 53.04% after fine-tuning. In comparison, syntax scores were slightly higher, starting at 50.46% for the base model and rising to 53.65% for the fine-tuned model. Collectively, these are the lowest scores across all ITALIC domains, emphasising the particular difficulty of foundational linguistic understanding in Italian.

2.4 - Comparing Multilingual & Monolingual Model Performance

Recent research has established clear performance hierarchies between different model types. According to both ITALIC findings [Seveso et al., 2025] and complementary studies [Fan et al., 2025, Polignano et al., 2023], multilingual models consistently outperform monolingual Italian models, particularly when the monolingual models are trained from scratch rather than fine-tuned from existing multilingual foundations.

This pattern is evident in ITALIC results, where ground-up Italian models like Minerva 7B (41.55% overall) and Modello Italia 9B (50.53% overall) significantly underperformed multilingual alternatives [Seveso et al., 2025]. The superior performance of multilingual models stems from their ability to leverage cross-lingual knowledge transfer, where concepts learnt through one language can be applied when responding in another language [Fan et al., 2025; Polignano et al., 2023].

The exception to this pattern involves models fine-tuned from multilingual foundations rather than trained from scratch. Llama 3.1 8B Ita demonstrates this advantage, outperforming most ground-up Italian models whilst maintaining access to multilingual knowledge representations [Seveso et al., 2025]. This clearly highlights that the optimal approach to achieving cultural alignment is by building upon the foundations of multi-lingual models rather than building mono-lingual models from scratch.

2.5 - Identified Gaps

2.5.1 - Discrepancy Between Cultural & Linguistics in Smaller Models

A significant finding from the ITALIC benchmark is the performance gap between tasks requiring cultural knowledge and those requiring linguistic understanding. This discrepancy is particularly pronounced in smaller-scale, open-weight models [Seveso et al., 2025]. While large-scale proprietary models like Claude 3.5 Sonnet exhibit a minimal gap (1.39 percentage points between Culture and Language scores), this difference becomes substantially larger in smaller and/or open models. For example, Llama 3.1 405B has a discrepancy of 4.98%, which widens to a significant 9.72% in Llama 3.1 8B. This trend demonstrates that as model size decreases, the relative weakness in handling the structural and grammatical rules of a language becomes more acute compared to performance on cultural knowledge. This highlights a key research gap: understanding why smaller models struggle disproportionately with linguistic tasks and developing targeted interventions to close this specific performance gap.

2.5.2 - Limited Analysis of Reasoning Model Benefits

The current literature, including the foundational ITALIC benchmark study, has not yet evaluated the performance of modern reasoning-capable models on Italian cultural and linguistic tasks. The models assessed in the paper are primarily standard LLMs, and there is no analysis of newer architectures that are explicitly designed to "think step by step" before generating an answer. These include proprietary models (like GPT-4o, Claude 4 and GPT-o3) and open-weight alternatives (like DeepSeek R1, Magistral, and Qwen3). Chain-of-Thought (CoT) encourage a model to break down a question into intermediate steps, a process that could be beneficial for navigating the complexities of Italian linguistics and to use the existing knowledge more effectively. It is plausible that activating a model's reasoning capabilities could, on its own, improve performance on difficult linguistic tasks by allowing for more deliberate processing, thereby narrowing the performance gap between cultural and linguistic understanding without the need for extensive fine-tuning. This project aims to directly investigate this hypothesis by systematically benchmarking such models and of various sizes, an area currently unexplored in the context of Italian cultural alignment.

2.5.3 - Weaknesses in Linguistic Capabilities

The ITALIC benchmark reveals that morphology, orthography, and syntax are consistently the weakest areas for LLMs in Italian [Seveso et al., 2025]. These findings are consistent with broader research, which shows LLMs struggle with morphologically complex languages and can suffer a drop in language understanding when working in Italian, even if their core reasoning skills remain [Ismayilzada et al., 2025; Puccetti et al., 2025]. Morphology consistently emerges as the most difficult domain for the models. The average accuracy across all tested models in morphology is only 55.99%. For smaller models like the base Llama 3.1 8B, the performance is even lower at just 40.00%. Orthography is the second most challenging domain, with an average accuracy of 62.09% across all models in the ITALIC benchmark. Again, smaller models struggle significantly in this area. Syntax is the third area of notable weakness. While the average accuracy is slightly higher at 64.37%, it still lags behind performance on tasks requiring cultural knowledge. The lack of effective, targeted methods to improve these specific linguistic abilities in Italian LLMs highlights a clear and important research gap.

3 - Background Theories

3.1 - Transformer Architecture

The Transformer architecture [Vaswani et al., 2017] forms the foundational backbone for virtually all modern LLMs, including those used in this project. It revolutionised the field by replacing the sequential processing of older models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). RNNs struggled with slow, token-by-token computation and had difficulty capturing long-range context in text. The Transformer overcame these limitations by abandoning recurrence in favour of a fully parallelisable mechanism known as self-attention [Vaswani et al., 2017].

The self-attention mechanism allows the model to weigh the importance of different words in a sentence simultaneously when processing a single word. This is achieved through several key components. Each word is represented by three vectors: a Query (Q), representing the current word's request for context; a Key (K), which acts as a label for other words; and a Value (V), containing the word's actual information. The attention score, which signifies relevance, is calculated by taking the dot product of the Query with all other Keys. This process is captured by the equation:

This mechanism allows the model to process entire sequences in parallel, drawing information from the entire sequence at once [Vaswani et al., 2017].

The Transformer also employs Multi-Head Attention, which runs multiple self-attention processes in parallel. Each of these "heads" learns to focus on different types of relationships in the text, such as syntactic dependencies or semantic similarities. The outputs are then combined, resulting in a much richer and more nuanced understanding of the language [Vaswani et al., 2017].

To maintain sequential information, the Transformer injects positional encoding vectors into the input. These provide crucial information about each token's position in the sequence [Vaswani et al., 2017].

The architecture also includes Feed-Forward Networks for additional non-linearity. To enable deep training, the architecture uses residual connections and layer normalisation, which stabilises the learning process and prevents gradients from vanishing [Vaswani et al., 2017].

3.1.1 - Architectural Evolution & Specialisation

While the original Transformer was designed with an encoder-decoder structure for machine translation, its modularity spurred an architectural evolution. This led to specialised variants that underpin most modern LLMs:

Encoder-only models, such as BERT, use the Transformer's encoder stack to pre-train deep bidirectional representations. This makes them exceptionally powerful for Natural Language Understanding (NLU) tasks where a deep comprehension of the full context is required [Devlin et al., 2019].

Decoder-only models, such as the GPT series, use the Transformer's decoder stack. These models are autoregressive, generating text one token at a time based on previously generated tokens. This makes them highly effective for Natural Language Generation (NLG) tasks [Radford et al., 2018]. The models evaluated in this project (including Llama, Mistral/Magistral, and Qwen) are all descendants of this decoder-only lineage.

3.1.2 - Comparison with Pre-Transformer Neural Architectures

Before the Transformer, NLP was dominated by architectures with significant limitations. RNNs, including more advanced variants like LSTMs and GRUs, processed text sequentially, which created a computational bottleneck that hindered parallelism and made it difficult to capture long-range dependencies [Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997; Chung et al., 2014]. CNNs offered parallelism but could only capture context within a limited local window, struggling with variable-length relationships in text [Kim, 2014]. The Transformer superseded these models because its self-attention mechanism processes all tokens in parallel, allowing information to flow globally across the entire sequence in a single step. This solved both the sequential bottleneck of RNNs and the limited receptive field of CNNs, enabling the massive scale and emergent capabilities of modern LLMs.

3.1.3 - Recent Progress in Large Language Models

The last five years have seen LLMs scale dramatically, with increased size and innovations like instruction-tuning and Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) unlocking new capabilities [Brown et al., 2020]. However, the frontier of LLM development has shifted from pure scale to enhancing specific cognitive capabilities.

This has led to a new generation of models explicitly architected for advanced reasoning, such as GPT-4o, Claude 4, and Gemini 2.5 Pro [Bubeck et al., 2023]. A key innovation in this space is the development of hybrid reasoning models, which can operate in a fast, standard mode for simple queries or switch to a more computationally intensive "thinking" mode for complex problems. Investigating whether these advanced reasoning techniques can be leveraged to improve performance on complex linguistic tasks is the central question of this project's first hypothesis. The following section delves into the specific techniques that enable this advanced reasoning.

3.2 - Reasoning Models

Standard LLMs built on the Transformer architecture are trained to predict the next word in a sequence. While this makes them proficient at language tasks, it is insufficient for problems requiring logical deduction. A deep understanding of these techniques is fundamental to this project's first hypothesis: that the latent reasoning capabilities of modern LLMs can be leveraged to close the performance gap between cultural and linguistic understanding. For tasks in mathematics or commonsense reasoning, simply predicting the most statistically likely word often fails to produce a correct solution. This limitation is shown by "flat scaling curves," where simply increasing a model's size does not significantly improve performance on complex reasoning without a fundamental shift in methodology [Wei et al., 2022].

The ability for complex reasoning is not an automatic result of scale; it must be deliberately prompted or engineered. In this context, "reasoning" is the ability to break down a problem into a series of intermediate steps that logically lead to a conclusion. The introduction of CoT prompting was a foundational shift, demonstrating that the latent reasoning abilities of large models could be unlocked by guiding them to externalise their problem-solving process [Wei et al., 2022]. This success has led to the development of specialised reasoning models that are explicitly trained and architected for complex reasoning.

3.2.1 - Foundational Techniques for Eliciting Reasoning

CoT prompting works by encouraging a model to generate a sequence of intermediate steps before the final answer. This reframes the task from a single, difficult inference to a series of simpler, incremental predictions. Instead of a large cognitive leap, the model performs a sequence of more manageable next-token predictions, effectively allocating more computation to the problem by generating a longer thought process. This is typically implemented via few-shot CoT, where the model is given examples of solved problems, or zero-shot CoT, where a simple instruction like "Think step by step" is used.

A critical finding is that CoT is an emergent property of model scale; its benefits only appear in models with around 100 billion parameters or more and can degrade the performance of smaller models [Wei et al., 2022]. However, a single reasoning chain is brittle, as one early error can corrupt the entire output. To address this, self-consistency was introduced as a decoding strategy [Wang et al., 2022]. It generates multiple, diverse reasoning paths for the same problem and determines the final answer by a majority vote. This ensemble-like approach significantly improves robustness, yielding gains of +17.9% on the GSM8K benchmark, but at the cost of increased computation.

3.2.2 - Advanced Reasoning Frameworks & Strategies

The linear, step-by-step nature of CoT is ineffective for tasks that require planning or exploration. Tree of Thoughts (ToT) provides a more powerful framework by modelling problem-solving as a search through a tree of possibilities, which is closer to human cognition [Yao et al., 2023]. In the ToT framework, an LLM is used to generate multiple potential next steps ("thoughts"), a checker module evaluates their validity and promise, and a controller manages the search process using algorithms like breadth-first or depth-first search.

The most significant feature of ToT is its ability to backtrack. If a path of reasoning is found to be unpromising, the controller can discard that branch and explore an alternative from a previous state. This capacity for systematic exploration and error correction allows ToT to solve complex planning problems, such as the Game of 24, that are often intractable for linear CoT methods [Yao et al., 2023]. This represents a move from simple generation to a more structured and robust problem-solving paradigm.

3.2.3 - Mitigating Inference Time & Cost

While early reasoning techniques focused on accuracy, their high latency and token consumption are barriers to practical use. This has driven innovation toward more efficient reasoning.

One key technique is Chain of Draft (CoD), which challenges the assumption that more verbose reasoning is better. Inspired by how humans often jot down only key intermediate results, CoD prompts the model to generate minimalistic yet informative reasoning steps. This approach significantly reduces latency and cost, often with no loss in accuracy [Tian et al., 2025].

Another strategy, Confidence-Informed Self-Consistency (CISC), targets the high cost of standard self-consistency. After generating each reasoning path, the model is prompted to evaluate its confidence in that path's correctness. The final answer is then determined by a weighted majority vote, giving more influence to high-confidence paths. This allows the system to converge on the correct answer with over 40% fewer reasoning paths, making the technique more practical and scalable [Taubenfeld et al., 2025].

3.2.4 - Training & Architectures

The latest reasoning models are explicitly trained for this capability, moving beyond prompting alone. While Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) on reasoning examples is effective, it is limited by the quality of static datasets. Reinforcement Learning (RL) offers a more scalable paradigm where the model learns through trial-and-error, receiving feedback on its generated reasoning. A key innovation is Reinforcement Learning from Verifiable Rewards (RLVR), which uses a reward signal from a deterministic, objective verifier, such as checking a maths answer for correctness or running code against unit tests. This provides a clear, ground-truth-aligned signal that allows the model to autonomously discover correct reasoning paths [Guo et al., 2025].

To implement this efficiently, models like DeepSeek and Magistral use algorithms such as Group Relative Policy Optimisation (GRPO). GRPO streamlines RL by removing the need for a separate value model, instead calculating the advantage of a response based on its reward relative to the average reward of other sampled responses [Mistral-AI, Rastogi, et al., 2025]. The DeepSeek R1 model demonstrated that a pure RLVR approach could lead to the autonomous emergence of sophisticated behaviors like self-verification, boosting its AIME benchmark score from 15.6% to 71.0% [Guo et al., 2025]. Similarly, Mistral's Magistral was trained with RL to increase its AIME score by 50% and was specifically designed for multilingual reasoning by including translated problems and a language consistency reward in its training data [Mistral-AI, Rastogi, et al., 2025].

Alongside training innovations, new architectures allow models to dynamically allocate computation at inference time. Google's Gemini 2.5 Pro has an integrated "thinking process" that can perform tens of thousands of extra forward passes to explore a problem, with the amount of thinking calibrated to the task's complexity [Google AI, 2025]. Anthropic's Claude 4 features distinct operational modes: a standard mode for fast responses and an "extended thinking mode" for deep reasoning, which can also integrate external tools like a code interpreter [Anthropic, 2025]. These architectures enable a more intelligent allocation of resources, balancing performance with efficiency.

3.2.5 - Multilingual Reasoning Capabilities

As LLMs are deployed globally, their ability to reason across multiple languages is critical. Models like the Qwen2 series and Mistral's Magistral have been explicitly trained for this [Qwen Team, 2024a]. Magistral incorporated translated mathematics and coding problems into its RL training data and used a language consistency reward to ensure it could reason natively in languages like French, Spanish, and German [Mistral-AI, Rastogi, et al., 2025].

Despite these efforts, a performance gap persists between English and other languages. The Magistral Medium model, for instance, sees its performance on translated versions of the AIME benchmark drop by 4.3% to 9.9% compared to English [Mistral-AI, Rastogi, et al., 2025]. This suggests that reasoning is not a purely abstract, language-agnostic skill in current LLMs. Instead, it appears deeply connected to the specific linguistic patterns in the training data, and the learned associations between phrasing and logical operations in one language do not always transfer perfectly to others [Ahuja et al., 2025].

3.2.6 - Reasoning vs. Non-Reasoning Models

Reasoning models offer clear advantages for complex problems. They are more accurate and reliable than standard models. Their step-by-step output also provides a window into their process. This makes it easier for users to check the logic, spot errors, and build trust in the final answer. In contrast, normal models provide direct answers which is faster but offers no justification [AiSDR, 2025].

However, these benefits come with significant trade-offs. Reasoning models are slower and more expensive to run because generating long thought processes uses more computation. The "interpretability" they offer must also be viewed carefully. The reasoning path a model shows might be a convincing story created after the answer is found, not a true reflection of how it solved the problem [Turpin et al., 2024]. The pursuit of truly verifiable and causally-grounded reasoning (ensuring the logic is sound and factually correct) remains a key challenge. A deeper issue is the trade-off between specialisation and generalisation. Training a model to excel at reasoning can make it worse at other tasks, like following conversational instructions [Seveso et al., 2025]. This suggests that AI "intelligence" is not a single quality but a collection of skills that can compete with each other. This is why hybrid models like Claude, Qwen and Magistral (which can switch between a fast, general mode and a slow, reasoning mode) are being developed. They aim to provide the best of both worlds.

3.3 - Low Rank Adaptation (LoRA)

3.3.1 - PEFT

Traditional method, Full Fine-Tuning (FFT), involves updating all of a model's parameters on a new, task-specific dataset. While effective, this approach has become increasingly impractical for modern LLMs, which can have billions of parameters (or even hundreds of billions). The computational cost, memory requirements, and storage demands of FFT are prohibitive for most researchers and organisations, as each fine-tuned model is a complete, multi-gigabyte copy of the original [Hu et al., 2022]. Furthermore, FFT carries a significant risk of "catastrophic forgetting," where the model loses valuable general-purpose knowledge acquired during pre-training as it learns the new task [Kirkpatrick et al., 2017].

(PEFT). The core principle of PEFT is to freeze the vast majority (often over 99%) of the pre-trained model's parameters and only train a small number of new or existing parameters. This dramatically reduces computational and storage costs, making LLM customisation more accessible while often achieving performance comparable to FFT [Hu et al., 2022]. This technique is central to the project's second phase, providing the parameter-efficient methodology required to test the hypothesis that linguistic improvements can be achieved without catastrophic forgetting.

3.3.2 - LoRA

LoRA is a particularly elegant and effective PEFT technique [Hu et al., 2022]. It is based on the hypothesis that the change in a model's weights during adaptation to a new task has a low "intrinsic rank" [Hu et al., 2022]. This means the adjustments required to specialise a model are not complex and diffuse but are concentrated and can be represented efficiently in a lower-dimensional subspace.

3.3.3 - LoRA Mechanism

LoRA injects trainable rank decomposition matrices into each layer of the Transformer architecture, creating a parallel module. This module represents the change in weights (ΔW) as the product of two much smaller, "low-rank" matrices: A and B. During training, the original weight matrix remains frozen and does not have its gradients updated. Only the parameters of the newly introduced matrices A and B are trained [Hu et al., 2022].

The forward pass is modified to combine the output from the original frozen path and the new, trained path:

This approach is highly parameter-efficient. For example, adapting a 1000×1000 weight matrix (1 million parameters) using LoRA with a rank of would only require training parameters, a reduction of over 99% [Hu et al., 2022].

3.3.4 - Advantages of LoRA

Once training is complete, the learned matrices can be mathematically merged with the original weights by calculating . The resulting model has the exact same architecture and parameter count as the original, making it highly efficient for deployment [Hu et al., 2022].

This ability to merge adapters is a crucial factor for this project [Hu et al., 2022]. This allows for the creation of many small, task-specific "adapters" (often just a few megabytes in size) that can be swapped out to modify the model's behaviour without altering the base model. This is orders of magnitude more efficient in terms of computational cost, memory usage, and storage [Hu et al., 2022]. By freezing the base model, it also serves as a strong regulariser that mitigates catastrophic forgetting [Hu et al., 2022], while often matching or exceeding FFT's performance on a wide range of tasks [Long et al., 2024]. LoRA avoids the inference latency added by methods like Adapter Tuning [Houlsby et al., 2019] and circumvents the optimization and context-window consumption issues associated with Prefix-Tuning [Li and Liang, 2021; Hu et al., 2022; Vgontzas et al., 2023]. Therefore, LoRA was the most suitable fine-tuning strategy, as its efficiency, zero-latency characteristic, and ability to preserve general knowledge were crucial for achieving the project's objectives.

3.3.4.1 - Choice for This Project

Its efficiency makes it feasible to conduct targeted experiments on smaller models to address specific linguistic weaknesses, such as Italian morphology. Its zero-latency characteristic and ability to preserve general knowledge are crucial for achieving the objective of improving linguistic performance without destroying the model's existing capabilities.

3.3.5 - Disadvantages of LoRA

LoRA is not without limitations. Its performance can lag behind full fine-tuning because the low-rank assumption is not always valid, which can cause an accuracy gap on complex domains like code and maths compared to full fine-tuning [Biderman et al., 2024]. Performance is also highly sensitive to hyperparameters, requiring careful tuning to approach the results of a full finetune [Biderman et al., 2024]. From a practical standpoint, LoRA presents memory challenges; serving thousands of small adapters can exhaust GPU memory, making it "infeasible" at scale [Brüel-Gabrielsson et al., 2025]. Furthermore, standard LoRA training can still demand substantial RAM for very large models, which necessitated the development of more memory-efficient variants like QLoRA [Dettmers et al., 2023].

3.4 - Quantisation

Quantisation is a model compression technique that addresses this issue. It reduces the numerical precision of a model's parameters, for instance, from 32-bit floating-point numbers to more efficient 4-bit integers. This process results in a much smaller memory footprint and can speed up computation. However, this process is inherently lossy and can introduce minor errors, potentially degrading a model's predictive performance.

For this project, quantisation is a crucial enabling technology. It makes it feasible to run experiments on larger models, such as the 24-billion-parameter Magistral-Small, on hardware with limited VRAM. While this introduces a risk of slight performance misalignment for the Magistral-Small model, it is an acceptable trade-off as it serves as a control, and this was a necessary compromise to ensure the experiment was computationally feasible. Specifically, this project utilises QLoRA, a method that combines quantisation with the parameter-efficient fine-tuning approach discussed in the next section. QLoRA allows for backpropagation through a frozen, 4-bit quantised model into a small set of trainable adapters, drastically reducing memory requirements during training with minimal impact on performance [Dettmers et al., 2023].

4 - Objectives

4.1 - Principal Objectives

The primary objective is to determine if the advanced reasoning capabilities found in newer LLMs can improve performance on complex Italian linguistic tasks. This research will test the hypothesis that these same reasoning skills, typically used for logical problems like mathematics, can also be applied to navigate the grammatical rules of the Italian language.

The second objective addresses a practical challenge. The reasoning process is slow and computationally expensive. Therefore, this project aims to improve the models' faster, non-reasoning mode through fine-tuning. The goal is to enhance linguistic performance so that the model is effective for everyday tasks without needing to "think".

However, this fine-tuning creates a critical risk. Specialised training can cause a model to lose its general abilities, including its core reasoning skills. The final and most important objective is therefore to solve this trade-off. The project aims to develop and validate a novel fine-tuning methodology that improves non-reasoning linguistic performance while also preserving and enhancing the model's advanced reasoning capabilities.

4.2 - Secondary Objectives

4.2.1 - Objective 1: Establish Validated Baseline

To support the primary objectives, the first task is to establish a validated baseline. This involves replicating the published results from the ITALIC benchmark for two key models. The first model is Llama 3.1 8B Ita, a variant of Llama 3.1 8B fine-tuned on Italian data and the best-performing small-scale model in the original study. The second is Mistral NeMo (12B parameters) which is a multilingual model that will serve as a control.

The goal is to consistently reproduce their benchmark scores, for both the final average accuracy and for each of the 12 individual categories, with a deviation of no more than 1.5%.

This validation is critical because the proven methodology can then be confidently applied to benchmark subsequent models, such as the reasoning-capable models, ensuring that any observed performance differences are due to the models themselves and not variations in the experimental setup.

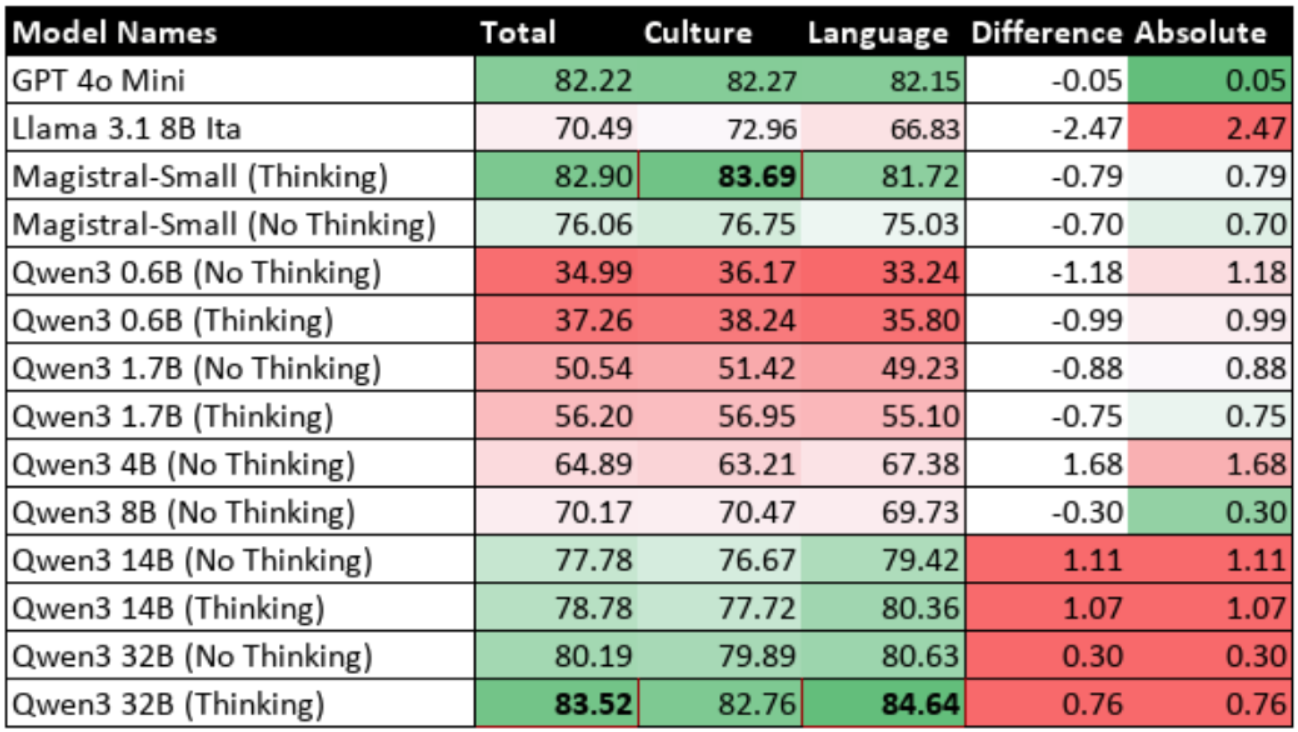

4.2.2 - Objective 2: Evaluate Reasoning-Capable Models (Reasoning Disabled)

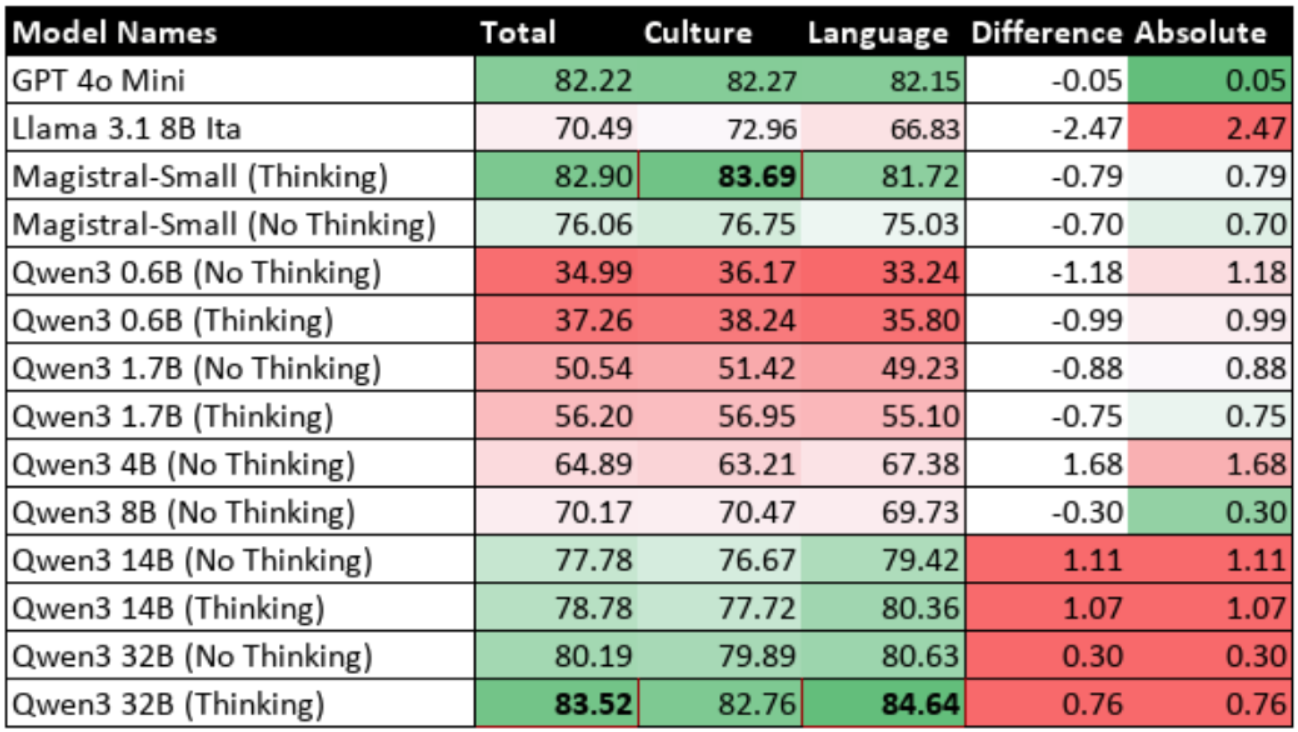

The next step is to evaluate modern hybrid reasoning models with their reasoning capabilities disabled. This will involve benchmarking the Qwen3 series of models, which are available in various sizes allowing for an analysis of scaling effects. To ensure the findings are not specific to one model family, Magistral-Small (available only as 24B parameters) model will also be evaluated.

This step is important because it establishes a baseline performance for the general architecture of these models. It makes it possible to understand how much of any performance gain is from the reasoning process itself, rather than from the model's underlying design. The results from this evaluation will be directly compared against the performance of the same models when their reasoning is enabled.

4.2.3 - Objective 3: Evaluate Reasoning-Capable Models (Reasoning Enabled)

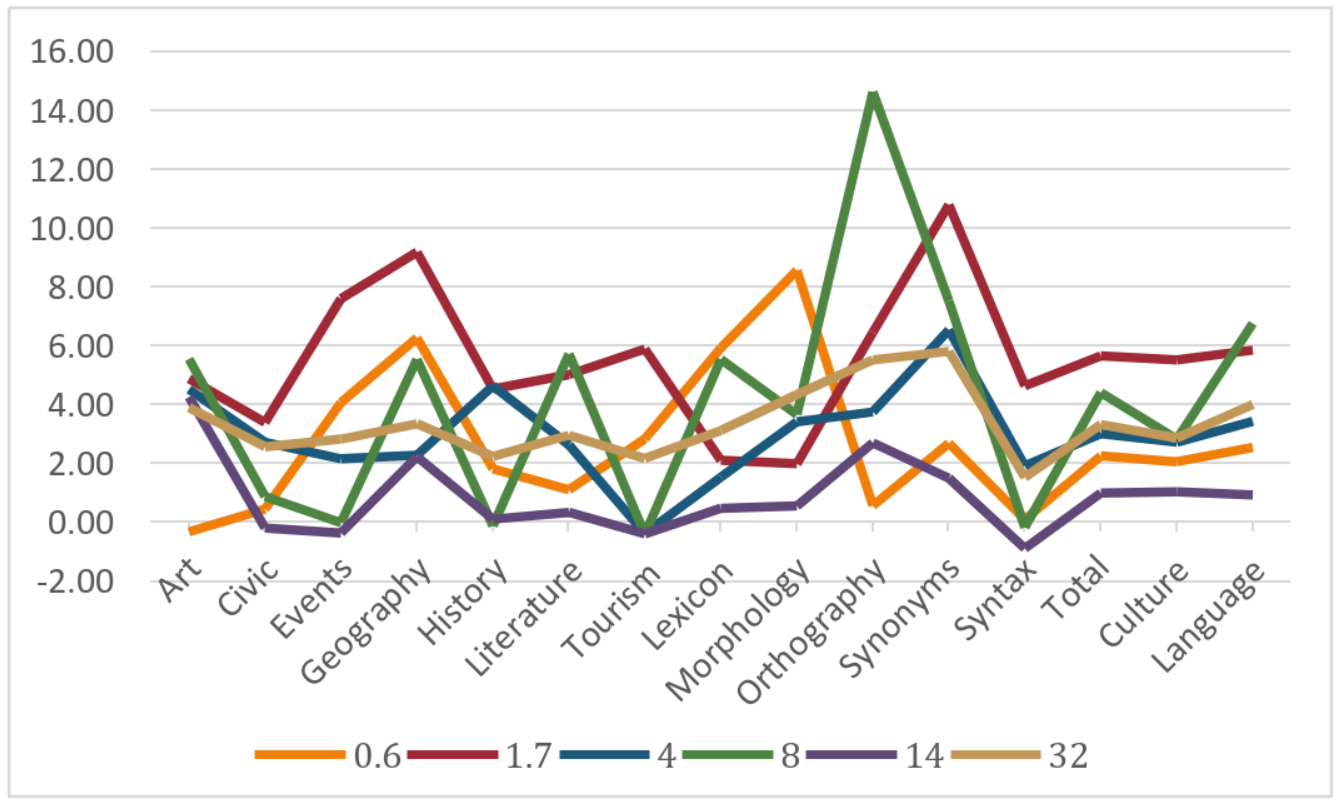

Following the baseline evaluation, the same reasoning-capable models (Qwen3 series and Magistral-Small) will be benchmarked again, but this time with their reasoning capabilities enabled. The primary goal is to measure the performance difference between the reasoning-enabled and reasoning-disabled states. This will show how much the reasoning process contributes to the models' performance.

A key part of this analysis will be to check if the performance gap between cultural knowledge and language understanding closes. If reasoning does lead to significant improvements, a qualitative analysis will be performed. This involves comparing questions that were answered incorrectly when reasoning was disabled to those that are now correct to understand how the reasoning process helps solve complex linguistic problems. Completing this evaluation will fulfil the first primary objective of the research.

4.2.4 - Objective 4: Implement Supervised Fine-Tuning

The next step is to fine-tune the models. This will be done using the regular LoRA technique. The reasoning models (Qwen3 and Magistral-Small) will be fine-tuned on the Mult-It dataset, a broad Italian question-answer dataset that is well-aligned with the ITALIC benchmark format. This dataset covers many of the known linguistic weaknesses of the models. For comparison, a non-reasoning model, Llama 3.1 8B Ita, will also be fine-tuned as a control. The specific aim of this fine-tuning is to improve performance in the three weakest linguistic areas: morphology, orthography, and syntax.

4.2.5 - Objective 5: Evaluate Fine-Tuned Models

The final task is to benchmark the models after fine-tuning. The fine-tuned reasoning models will be evaluated twice using the same established pipelines: once with reasoning disabled and once with reasoning enabled. The fine-tuned Llama 3.1 8B Ita control model will also be benchmarked.

First, the evaluation will measure the performance improvement with reasoning disabled to see if the fine-tuning successfully closed the gap with cultural and commonsense knowledge. To prevent catastrophic forgetting, it is also crucial that the models do not perform worse in these existing areas of strength.

If the gap is closed, the analysis will then focus on the impact to the reasoning process itself. It will explore whether the fine-tuned models can combine the new linguistic knowledge with their reasoning, whether there is no effect, or if reasoning performance has worsened. A detailed analysis will be conducted to understand the reasons behind these outcomes.

5 - Specifications

5.1 - General Project Specifications

These requirements apply across all phases of the project.

- Model Architecture: All models selected must be publicly available, open-weight, decoder-only LLMs based on the Transformer architecture.

- Computational Constraints:

- Models selected for benchmarking must have fewer than 35 billion parameters.

- Models selected for fine-tuning must have fewer than 15 billion parameters due to higher memory overhead.

- Benchmark: All evaluations must use the ITALIC benchmark in a zero-shot setting [Seveso et al., 2025].

- Hardware & Software:

- All experiments must be executable on a single NVIDIA GPU with up to 40GB of VRAM. Most of the experiments can be carried out on a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 with 24GB of VRAM. At least CUDA 12.1 is needed.

- The software stack must use standard open-source libraries like PyTorch and Hugging Face transformers, peft, and trl.

- Answer Extraction: An automated, REGEX-based parser is required to extract and score answers from model outputs with high accuracy.

5.2 - Phase 1: Baseline Replication Specifications

This initial phase is designed to validate the experimental framework.

- Model Requirements: Two non-reasoning models from the original ITALIC study must be used.

- Llama 3.1 8B Ita (DeepMount00/Llama-3.1-8b-ITA): An 8-billion-parameter model specifically fine-tuned for Italian.

- Mistral NeMo (mistralai/Mistral-Nemo-Instruct-2407): A 12-billion-parameter general-purpose multilingual model.

- Process Requirements: Each model must be benchmarked three times to assess consistency.

- Performance Criteria: This phase will be considered successful if the evaluation pipeline is validated.

- The replicated average accuracy scores must be within a ±1.5% margin of the results published in the ITALIC paper.

- The results must show a low standard deviation across the three runs, ensuring the findings are reproducible and statistically sound.

5.3 - Phase 2: Reasoning Capability Analysis Specifications

This phase is analytical and aims to determine if reasoning capabilities affect performance on linguistic tasks.

- Model Requirements: The evaluation requires a set of hybrid reasoning models capable of operating with and without a reasoning process. This is crucial to isolate architectural improvements from the effects of reasoning.

- Qwen3 Series: Models of varying sizes (Qwen/Qwen3-0.6B, Qwen/Qwen3-1.7B, Qwen/Qwen3-4B, Qwen/Qwen3-8B, Qwen/Qwen3-14B, Qwen/Qwen3-32B) must be used to analyse scaling effects.

- Magistral-Small (mistralai/Magistral-Small-2506): A 24-billion-parameter reasoning model from a different family will serve as a control to ensure findings are not architecture-specific.

- Process Requirements: Each model must be benchmarked twice: once with reasoning disabled to set a baseline, and once with reasoning enabled.

- Performance Criteria: Success in this phase is defined by the quality of the analysis.

- The analysis must provide a clear, data-driven and statistically significant conclusion on whether reasoning improves, degrades, or has no effect on linguistic tasks.

- The analysis must also provide a qualitative explanation for why these changes occur, based on the models' outputs.

5.4 - Phase 3: Fine-Tuning Intervention Specifications

This phase is contingent on Phase 2 demonstrating that reasoning provides a performance benefit. The goal is to create a more efficient model by enhancing its non-reasoning capabilities while still making reasoning accessible for more complex tasks.

- Model Requirements: The fine-tuning process must use the hybrid reasoning models from Phase 2.

- Process Requirements: The intervention must use a parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) technique, specifically LoRA (due to its efficiency) to modify the models. The primary dataset for this process must be Mult-IT [Rinaldi et al., 2024].

- Performance Criteria: The fine-tuned model (the artefact) will be considered a success if it meets three simultaneous conditions:

- Improved Efficiency: The model's non-reasoning performance on linguistic tasks must show statistically significant improvement. This is critical for practical applications like customer service agents, where the latency and computational cost of the reasoning mode are prohibitive.

- Reasoning Preservation: The model's core reasoning capability must remain intact and functional. A loss of this ability constitutes a failure.

- Knowledge Preservation: The model must not exhibit catastrophic forgetting. Performance in cultural knowledge categories must not degrade significantly.

6 - Design

This chapter presents the architectural blueprint of the project. The entire experimental design is hypothesis-driven, structured in two main phases to systematically test the project's core claims. The first phase, Benchmarking, was designed to test the initial hypothesis that modern reasoning capabilities can improve performance on complex linguistic tasks. The second phase, Iterative Fine-Tuning, was designed as an experimental process to find the most effective way to enhance the model's efficient, non-reasoning performance while preserving its advanced reasoning capabilities.

6.1 - Benchmarking Design

The initial phase of the project was designed to systematically evaluate and compare the performance of various models on the ITALIC benchmark [Seveso et al., 2025]. This required a reliable experimental framework and a clear analytical strategy to test the first hypothesis. The process began by benchmarking the two models from the original ITALIC study to validate the pipeline. Following this validation, the reasoning-capable models were benchmarked with and without their reasoning modes enabled.

6.1.1 - Experimental Framework Architecture

The experimental framework was designed as a modular pipeline to ensure a standardised and repeatable process for benchmarking each LLM. This design allows for consistent data handling, prompting, inference, and evaluation. The same core pipeline was used for all non-reasoning evaluations to ensure consistency. The reasoning benchmark was a direct extension of this pipeline, also applied uniformly across all relevant models. This consistency was critical for making valid comparisons. A high-level overview of this pipeline is shown in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1: Experimental Pipeline Architecture

Figure 6.1: Experimental Pipeline Architecture

- ITALIC Dataset: The main benchmark for evaluating the models' alignment [Seveso et al., 2025].

- Prompt Templating Engine: Formats each question into a consistent zero-shot prompt. For standard evaluations, the prompt was identical to the one used in the original ITALIC paper to prevent the prompt from influencing the results. For reasoning evaluations, this prompt was extended with an aggressive instruction for the model to "think briefly". This was designed to elicit a thought process while preventing the excessively long and slow outputs that can occur with unconstrained reasoning.

- Model Inference Engine: All model inference was handled by the vLLM engine, chosen for its high-throughput batching and efficient memory management.

- Output Parsing & Answer Extraction: A REGEX-based parser was designed with multiple patterns to reliably handle the different output formats from models in both non-reasoning and reasoning modes. The parser was designed with multiple, ordered REGEX patterns to handle common variations (e.g.,

FINALE: B,Answer: B, or a standaloneB), ensuring robust and accurate extraction across different model outputs. An alternative approach, using a second language model to intelligently parse the output, was also considered. This was rejected because it would be significantly slower, less predictable, and would add unnecessary complexity to the pipeline compared to the deterministic REGEX method. - Scoring Module: Compares the extracted answer with the ground-truth answer.

- Results Aggregation & Analysis: Collates scores to calculate overall and category-specific accuracies.

6.1.2 - Model Selection Rationale

The selection of models was a core part of the experimental design, chosen to establish a valid baseline and to systematically test the project's hypotheses.

6.1.2.1 - Baseline Models

To ensure the validity of the experimental framework, two models from the original ITALIC study were selected to replicate the published results:

- Llama 3.1 8B Ita: Chosen as the primary baseline for a small-scale, language-adapted model.

- Mistral NeMo: Chosen as a control to validate accuracy of the framework.

6.1.2.2 - Reasoning-Capable Models

To investigate the project's central hypotheses, modern hybrid reasoning models were selected. This was a critical design choice, as these models allow reasoning to be toggled ON and OFF. This feature makes it possible to isolate the performance impact of the reasoning process itself from general architectural improvements. Purely reasoning-focused models like DeepSeek R1 were unsuitable because they do not offer this switchable functionality.

- Qwen3 Series (0.6B to 32B): This model family was chosen specifically to design an experiment for analysing scaling effects.

- Magistral-Small: This model was selected as a crucial control. As it belongs to a different architectural family, its inclusion was designed to ensure the project's findings were not architecture-specific. To maintain experimental consistency, this model was benchmarked with 4-bit quantization from the start, ensuring a fair comparison with its post-QLoRA fine-tuned version (which requires quantization).

6.1.3 - Comparative Analysis Design

The initial benchmarking was designed around two key comparisons:

- Baseline vs. Reasoning-Enabled Analysis: This analysis was designed to directly test the first project hypothesis. To isolate the impact of the reasoning process, the same models were tested in two distinct modes. This direct comparison allows for a quantitative measurement of the performance gain attributable solely to step-by-step thinking.

- Pre- vs. Post-Fine-Tuning Analysis: This comparison was conducted after each fine-tuning iteration to measure the effectiveness of the intervention. To facilitate this iterative cycle, the benchmarking framework was designed to load a locally stored LoRA adapter, merge it with the base model, and then run the full evaluation.

6.2 - Iterative Fine-Tuning Design

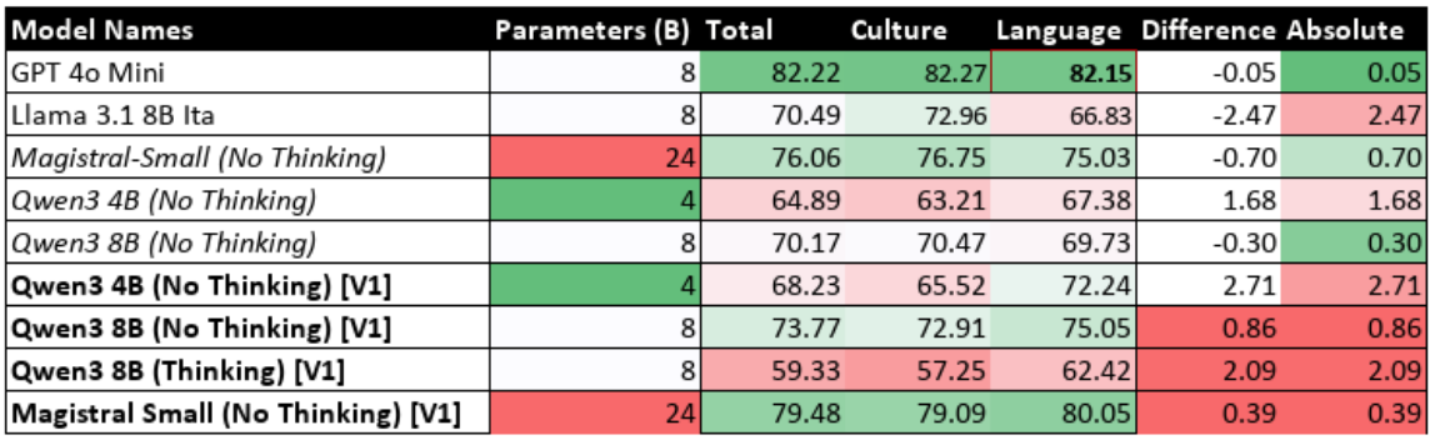

Following the initial benchmarking, a multi-stage fine-tuning process was designed to address the linguistic weaknesses identified in the reasoning models. This process was designed to test the second hypothesis: that a targeted intervention could enhance the efficient non-reasoning mode while preserving advanced reasoning capabilities. This was approached as an iterative experimental cycle. The initial experiment established a baseline, but its results revealed an unexpected and critical challenge, which required subsequent experiments to diagnose and solve.

To conduct these experiments, several models were selected for specific reasons. The Qwen3 4B, Qwen3 8B, and Magistral-Small models were chosen because they are all hybrid reasoning models. Qwen3 8B is the same scale as Llama 3.1 8B Ita, allowing for direct comparisons. To validate the intervention's effectiveness on a standard model, Llama 3.1 8B Ita was also fine-tuned as a non-reasoning control.

Figure 6.2: Fine-Tuning and Evaluation Cycle

6.2.1 - Core Fine-Tuning Technology Rationale

The foundational choices for the fine-tuning methodology were as follows:

6.2.1.1 - Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT)

PEFT was chosen over Full Fine-Tuning (FFT) as it is less computationally expensive and, crucially, carries a lower risk of catastrophic forgetting as discussed in Section 3.3.

6.2.1.2 - Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)

As established in the Background Theories Section 3.4, LoRA was selected as the specific PEFT method because it offers the best balance of parameter efficiency, high performance, and zero additional inference latency. For the Qwen3 models, standard LoRA was used. However, for the largest model, Magistral-Small (24B), the design was adapted to use QLoRA. This was a necessary choice dictated by the memory constraints as defined in the project specification, making fine-tuning feasible on the available hardware.

6.2.1.3 - Dataset Selection

The Mult-IT dataset was chosen for its direct alignment with the ITALIC benchmark's format and content [Rinaldi et al., 2024]. Alternative datasets were rejected after initial tests showed they were ineffective:

- MorphyNet: This dataset's format of inflection tables was fundamentally different from the multiple-choice task [Batsuren et al., 2022]. Training on it did not improve morphology performance and caused performance in other areas to degrade.

- BLM-CausI & BLM-Odl: These synthetic datasets used a narrow, rule-based prediction task [de la Cruz et al., 2024]. This format did not align with the broader knowledge required by ITALIC and failed to produce improvements, while also degrading performance.

6.2.2 - Iterative Approach to Hybrid Model Training

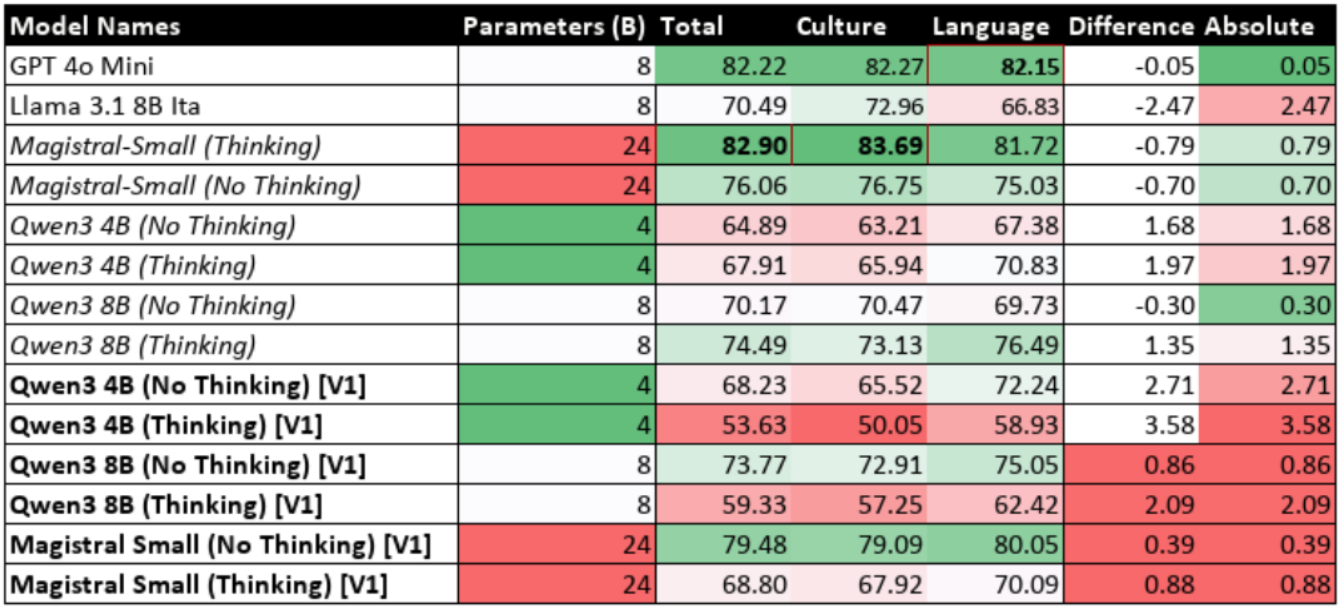

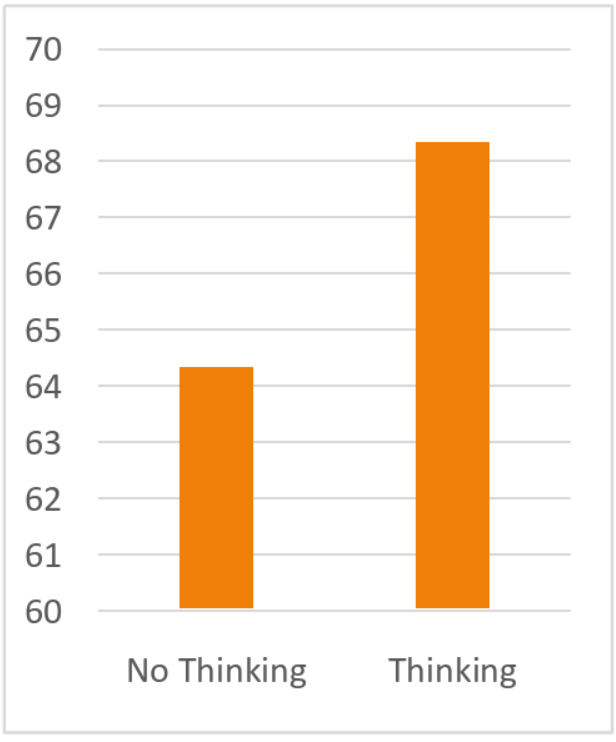

The project's central challenge (improving linguistic performance without destroying reasoning ability) was solved through an iterative experimental process:

- Experiment 1 (Regular PEFT): The cycle began by fine-tuning the models on the standard Mult-IT dataset. The subsequent benchmark evaluation confirmed this improved non-reasoning performance but revealed a catastrophic failure of the reasoning function.

- Experiment 2 (CoT-only PEFT): To diagnose and solve this issue, a second experiment was designed. This involved fine-tuning the model exclusively on a dataset of synthetic CoT examples. The benchmark results proved that this method restored reasoning but failed to improve non-reasoning performance. The synthetic CoT dataset was then merged with the original dataset, replacing duplicate questions to create the final hybrid dataset.

These preliminary experiments established that neither data format alone was sufficient. This led to the design of the final, novel hybrid approach.

6.2.3 - Final Hybrid Design (Novel Technique)

Figure 6.4: Synthetic Only Test Pipeline

Figure 6.5: Hybrid Training Pipeline

6.2.3.1 - Synthetic Data Generation

The hybrid dataset was created by augmenting the Mult-IT training data. The reasoning-enabled benchmarking pipeline was repurposed to run on the Mult-IT training set, generating CoT for approximately 18,000 correctly answered questions. This process was run independently for each model to create model-specific training data, respecting their unique internal monologues (e.g., Qwen3 thinking in English vs. Magistral in Italian). These 18,000 questions were used in experiment 2 without the standard Q&A samples first before this novel hybrid approach was finalised.

6.2.3.2 - Implementation

The hybrid training was implemented using the SFTTrainer from the trl library. A custom formatting function was designed to dynamically construct training examples using the model's chat template, inserting the synthetic thinking content for the augmented samples.

6.2.3.3 - Fine-Tuning as Regularisation

The final design mixes the ~18,000 synthetic CoT samples with the standard question-answer samples at a ratio of approximately 1:5. This treats the data as a form of bidirectional regularisation. The CoT samples periodically "remind" the model how to reason, while the more numerous standard samples prevent it from overfitting on the synthetic CoT. The final benchmark confirmed this design was highly successful.

6.2.3.4 - Alternative Design: Sequential Fine-Tuning

An alternative, sequential fine-tuning approach was also considered. This method involved two distinct steps. First, the model would undergo LoRA fine-tuning on the Mult-IT dataset to improve linguistic performance, just as in the first experiment. Afterwards, a second round of fine-tuning would be performed exclusively on the synthetic CoT data to restore the lost reasoning, similar to the second iteration.

However, this design was rejected because it is fundamentally suboptimal. The first training phase causes the model to suffer catastrophic forgetting of its original reasoning ability. The second phase would therefore not be preserving an existing skill but attempting to re-teach it from scratch using a limited dataset. The model's original reasoning was developed by its creators using sophisticated techniques like RLVR. Any re-taught ability would likely be a pale imitation of this powerful, pre-existing function. The final hybrid design is superior because it mixes both data types, allowing the model to learn new linguistic patterns while simultaneously being "reminded" how to reason, thus preserving its core capabilities.

7 - Methodology & Implementation

This chapter details the strategic methods and concrete technical implementations used in the project. It is structured in two phases. The first phase describes the design and validation of the analytical framework, a novel analytical contribution used to test the project's primary hypotheses on model performance. The second phase will detail the fine-tuning intervention that produced the final model artefacts using a novel hybrid training method.

7.1 - Phase 1: Analytical Framework for Benchmarking

7.1.1 - Benchmarking for Standard Non-Reasoning

7.1.1.1 - Methodology

The core method involved a standardised, zero-shot evaluation on the ITALIC benchmark [Seveso et al., 2025]. This approach was applied consistently across all models to ensure fair and reliable comparisons. The initial pipeline was carefully implemented based on the descriptions in the original ITALIC paper.

7.1.1.2 - Implementation

For the Llama, Mistral, and Qwen model families, the pipeline was implemented using the vLLM library. This choice was crucial for efficiently processing the 10,000-sample dataset on a single GPU. The codebase was built with a modular, class-based architecture (e.g., QwenBenchmark, Llama31Benchmark). This design simplified the workflow, making it easy to benchmark different model sizes and configurations without code repetition. Configuration for each experiment was managed through dedicated classes like QwenBenchmarkConfig, which allowed for precise control over parameters such as model_name, batch_size, and max_new_tokens.

A key difference in implementation was required for Magistral-Small. At the time of this project, vLLM did not fully support 4-bit quantisation. Therefore, its benchmarking pipeline was implemented using the standard Hugging Face transformers library with BitsAndBytesConfig for 4-bit nf4 quantisation, which was much slower. This pipeline was further optimised by enabling torch.compile and Flash Attention 2 where available, as configured in the MagistralBenchmarkConfig. A deliberate choice was made to use the tokenizer from mistralai/Mistral-Nemo-Instruct-2407, as this was the recommended and compatible tokenizer for the Magistral model at the time.

The QwenBenchmark, Llama31Benchmark, and MagistralBenchmark classes include a _merge_lora_adapters method, which uses the peft library to load a trained LoRA adapter, merge its weights with the base model, and then load the resulting merged model into vLLM for high-speed inference. This integrated workflow was essential for efficiently evaluating the artefacts produced in the second phase of the project.

7.1.1.3 - Benchmarking Hyperparameters

Most hyperparameters, such as batch_size, depend on the available GPU memory and do not affect the model's accuracy. For all non-reasoning evaluations, greedy decoding was used to ensure deterministic and consistent outputs as outlined in the ITALIC paper.

- For the Llama 3.1 8B Ita and Mistral NeMo models, the parameters were set to

max_new_tokens=350for both models andmax_length=8192for NeMo. - For the Qwen3 series and Magistral-Small, the parameters were set to

max_length=8192andmax_new_tokens=150.

7.1.2 - Benchmarking for Reasoning

7.1.2.1 - Methodology

The reasoning-capable models were benchmarked twice: once with reasoning disabled to set a baseline, and once with reasoning enabled to measure the performance change. This comparative method forms the basis of the project's novel analytical contribution.

7.1.2.2 - Implementation

- Qwen3 Series (Native API): The Qwen3 models provide a native API for enabling reasoning at the inference level. As shown in the

QwenReasoningBenchmarkclass, the call toself.model.chat()was modified to include the argumentchat_template_kwargs={"enable_thinking": True}. This flag instructs the model to generate its internal monologue within<think>tags. - Magistral-Small (Manual Template Construction): Magistral-Small requires a more manual implementation. Its tokenizer does not have an automated flag for reasoning. Instead, the

format_promptfunction in theMagistralFineTuningclass was engineered to manually construct the chat template according to the model's documentation, correctly placing the<think>tags between the[INST]...[/INST]user tags and the final answer.

7.1.2.3 - Reasoning Hyperparameters

For the reasoning-enabled benchmarks, a non-deterministic sampling strategy was required, as greedy decoding can cause performance degradation and endless repetitions in the models' thought processes [Qwen Team, 2024b].

- For the Qwen3 series, the models were configured with a Temperature of 0.6, TopP of 0.95, and TopK of 20, as recommended by the model's documentation [Qwen Team, 2024b].

- For Magistral-Small, the configuration used a temperature of 0.7 and top_p of 0.95 [Mistral AI, 2025].

7.1.3 - Prompting & Answer Parsing

7.1.3.1 - Methodology

A data handling protocol was essential for the integrity of the results. This involved using specific prompt templates for each evaluation mode and implementing parsers capable of accurately extracting answers from varied model outputs.

7.1.3.2 - Implementation

Two primary prompt templates were implemented. For non-reasoning evaluations, the prompt was identical to the one used in the original ITALIC paper. For reasoning-enabled evaluations, this was extended with an instruction for the model to "think briefly" and conclude with a FINALE: X tag, as detailed in the Specifications (Section 5.2).

This necessitated two separate answer extraction functions:

extract_answer_robust: A multi-pattern REGEX parser for standard outputs.extract_answer_with_reasoning: A more sophisticated parser with a hierarchical logic. It was engineered to first locate the closing<think/>tag and exclusively parse the text that followed. Only if this failed would it fall back to searching for other keywords likeFINALE:. This tailored approach was crucial for reliably handling the specific output format of the reasoning models.

This dual-parser system was a crucial implementation detail for ensuring accurate, automated scoring across all experimental conditions.

7.1.4 - Framework Validation & Reliability

7.1.4.1 - Methodology

The entire analytical framework was validated by replicating the published results for Llama 3.1 8B Ita and Mistral NeMo from the original ITALIC paper.

7.1.4.2 - Outcome

The framework successfully met the strict validation criteria. The replicated scores were highly accurate (e.g., within 0.17 percentage points for Llama 3.1 8B Ita). This successful validation provides definitive proof of the framework's reliability and confirms that the implementation is correct, serving as "adequate and effective testing". This trusted pipeline was then used for all subsequent evaluations.

7.2 - Phase 2: Fine-Tuning Intervention & Artefact Creation

This phase addressed the second hypothesis: that a targeted intervention could improve non-reasoning performance while preserving the model's core reasoning ability. The initial fine-tuning experiments revealed an unexpected and critical challenge (catastrophic forgetting of the model's reasoning abilities) which required the development of a novel hybrid training technique.

7.2.1 - LoRA Fine-Tuning

7.2.1.1 - Methodology

LoRA was chosen for its parameter efficiency and to mitigate the risk of catastrophic forgetting as detailed in Section 3.3. As detailed in Section 3.4, QLoRA was selected for the larger Magistral-Small model as it enables fine-tuning on quantised models, making the process feasible on the available hardware. The primary training data was the Mult-IT dataset [Seveso et al., 2025]. This choice was the result of a systematic investigation; preliminary experiments with more specialised datasets like MorphyNet proved ineffective as specified in section 6.2.1.3.

7.2.1.2 - Implementation

For Magistral-Small, the MagistralFineTuning class implemented QLoRA by first configuring a BitsAndBytesConfig for 4-bit nf4 quantisation, and then calling prepare_model_for_kbit_training to correctly prepare the quantized model for training. Training was managed by the SFTTrainer, which was configured to use an 8-bit AdamW optimizer to further manage memory usage. For all models, training efficiency was maximised by enabling sequence packing=True in the SFTConfig, which combines multiple short examples into a single sequence to improve throughput.

7.2.1.3 - LoRA Hyperparameters

To ensure the fine-tuning process can be reproduced, a consistent set of hyperparameters was used for the LoRA configuration, based on established best practices.

- Rank (r) = 24: This value was chosen as a balance between model capacity and parameter efficiency, sitting within the typical range of 8-64 used in successful LoRA implementations [Balandat et al., 2024; Hugging Face, 2025].

- Alpha (α) = 48: This follows the common practice of setting alpha to twice the rank [Hugging Face, 2025; Raschka, 2023].

- Dropout = 0.1: A standard dropout rate was applied to the LoRA layers for regularisation, which helps prevent overfitting [Wang et al., 2024].

- Target Modules: LoRA was applied to all linear layers within the model's attention blocks (

q_proj,k_proj,v_proj,o_proj) and the feed-forward networks (gate_proj,up_proj,down_proj).

7.2.2 - Iterative Experimental Process & Novel Hybrid Technique

The initial fine-tuning attempt revealed a critical flaw, necessitating an iterative experimental process that culminated in a novel hybrid training technique.

7.2.2.1 - Regular SFT

The first iteration used standard Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) on the Mult-IT dataset. While this successfully improved non-reasoning performance, it led to a catastrophic degradation of the reasoning function, as analysed in Section 9.4.1.2.

7.2.2.2 - CoT-Only Training

To diagnose and solve this issue, a second experiment was designed. This involved fine-tuning the model exclusively on a dataset of synthetic CoT examples. The benchmarking pipeline was adjusted to do so by simply passing the training dataset instead of the benchmarking dataset. A diagnostic training run on this synthetic data confirmed it successfully restored the model's reasoning ability (Section 9.4.2).

7.2.2.3 - Hybrid Training Method

These preliminary experiments established that neither data format alone was sufficient. This led to the design of the final, novel hybrid training method which is a novel technical contribution.

7.2.2.3.1 - Methodology

The hybrid dataset was created by augmenting the Mult-IT training data with synthetic CoT examples at a ratio of approximately 1:5, treating the CoT data as a form of regularisation, as discussed in the Design chapter.

7.2.2.3.2 - Implementation

The hybrid training was implemented using a sophisticated, adaptive training system. A ThinkingMode enum was used to control the training type. The configuration classes (e.g., QwenFineTuningConfig) were implemented to automatically adjust hyperparameters based on this mode; for example, when a thinking mode was enabled, max_length was increased and batch_size was reduced to accommodate the longer context windows. The format_prompt function then used this configuration to dynamically check each data sample for a 'thinking' key and apply the correct chat template for the respective model. This sophisticated, adaptive implementation was the key to successfully training a model that excelled in both non-reasoning and reasoning modes, as demonstrated in the final results (Section 9.4.3).

8 - Results, Analysis & Evaluation

This chapter measures the performance of the selected models against the stated objectives. The primary focus will be on the Qwen3 8B model, with other models serving as controls to validate the results. Statistical significance is shown using McNemar's Test with a significance threshold of p < 0.01. The code used for this computation is available in Appendix E.

8.1 - Baseline Validation